Copper shortage getting real

While experts say we could be looking at a 10-million-tonne deficit in at little as two years, in fact the shortfall could come even sooner, thanks to a number of supply-side events that have taken place recently.

20% of consumption

To start with, the predictions.

Some of the world's largest mining companies and metal traders are warning that by 2025, a massive shortfall will emerge for copper, which is now the world's most critical metal due to its essential role in the green economy. The deficit will be so large, The Financial Post stated last September, that it could itself hold back global growth, stoke inflation by raising manufacturing costs and throw global climate goals off course.

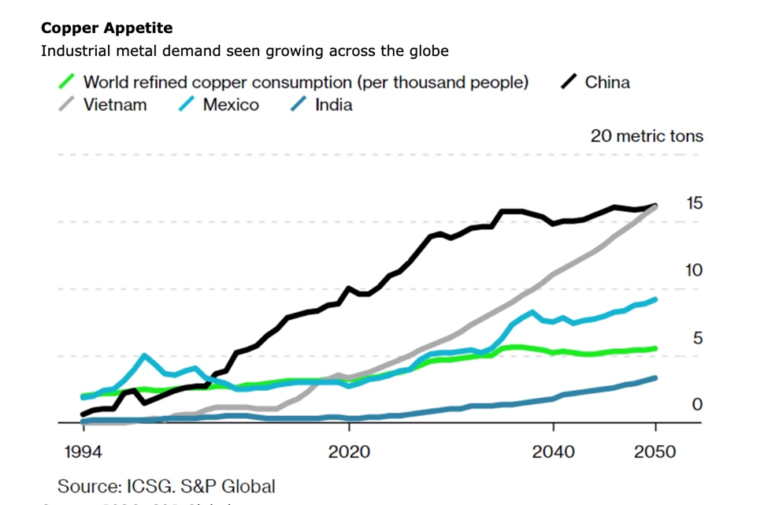

How big are we talking? Well, the speed at which copper demand outpaces supply will depend on the successful meeting of net-zero emission goals. According to a 2022 study by S&P Global, these goals will double the demand for copper to 50 million tonnes annually by 2035. Bloomberg New Energy Finance predicts demand will increase by more than 50% from 2022 to 2040.

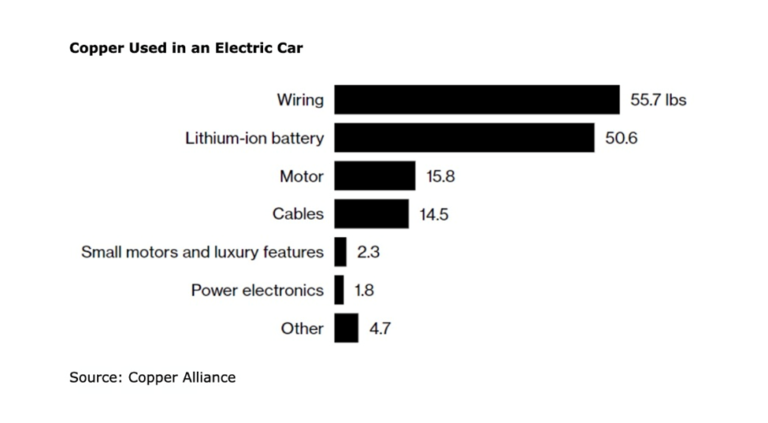

Along with the usual applications, in construction wiring and plumbing, transportation, power transmission and communications, there is the added demand for copper in electric vehicles and renewable energy systems.

Millions of feet of copper wiring will be required for strengthening the world's power grids, and hundreds of thousands of tonnes more, are needed to build wind and solar farms. Electric vehicles use over twice as much copper as gasoline-powered cars, which contain about 30 kg. There is more than 180 kg of copper in the average home.

"The energy transition is going to be dependent much more on copper than our current energy system," Daniel Yergin, S&P Global vice chairman, told CNBC. "There's just been the assumption that copper and other minerals will be there. … Copper is the metal of electrification, and electrification is much of what the energy transition is all about."

With so few new projects in the works, and as existing sources dry up, mine supply growth will peak around 2024, resulting in a historic deficit of 10 million tons (11,023,100 tonnes) in 2035. BloombergNEF predicts that by 2040, the mined-output gap (mines currently produce about 21Mt annually) will reach 14Mt, a shortfall that, without new supply, will have to be filled by recycling metal. Goldman Sachs says that mining companies will need to spend about $150 billion in the next decade, to address an 8-million-ton deficit.

Chilean state-owned Codelco is also predicting an 8Mt gap, but the world's biggest copper miner thinks it will come a year earlier, in 2032, as soaring demand continues to exceed new mine supply.

The International Study Group puts the coming deficit into perspective, noting that in 2021, the global copper shortfall was 441,000 tons, equivalent to less than 2% of demand for the refined metal, but enough to drive copper prices 25% higher. Using S&P Global's forecast, 2035's shortfall will be 10 times higher, at about 20% of consumption.

US$12,000 a ton by 2024: Goldman

As for what that could mean for prices, Goldman Sachs expects copper to average around $9,750 this year, with the average price jumping to $12,000 by 2024. Copper is currently quoting $8,400/t.

The influential bank noted that in 2022, sanctioned copper projects amounted to the lowest approval level in the last 15 years. "Even the extraordinarily high prices seen earlier in 2022 cannot create sufficient capital inflows and hence supply response to solve long-term shortages," it said, via Hindu Business Line.

Only two major copper mines were brought online between 2017 and 2021, according to the International Copper Study Group. Two greenfield projects, Ivanhoe Mines' Kamoa Kakula project in the DRC, and Anglo American's Quellaveco Mine in Peru, are currently ramping up production, but their output growth coincides with operational problems at existing mines, states BNE Intellinews.

The site notes output in Chile is set to fall by 5.8% this year. Codeleco's production declined in the first nine months of 2022 and is expected to fall further this year on worsening ore grades. Globally, the quality of ore is deteriorating, meaning output either slips or more rock has to be processed to produce the same amount.

First Quantum Minerals was forced to halt operations at its Cobre Panama Mine after failing to agree to royalties under a new contract.

Fitch Solutions said it was raising its copper price forecast to $8,500 a tonne from $8,400 previously, "as demand edges higher alongside a comparatively weaker supply outlook."

While copper lost its way for a few months last year, on recession fears and a strong US dollar, the red metal has pushed higher since the start of 2023, on hopes that Chinese demand returns following an easing of covid-19 restrictions, a potential slowing of US interest rate hikes, and as the dollar weakens.

Source: *****

Benedikt Sobotka, the CEO of Eurasian Resources, believes prices are set to rally even more, on the back of surging demand for copper used in energy transition technologies, matched against supply concerns.

"I am very long copper," Sobotka said in an interview with the Reuters Global Markets Forum, adding he expects a 10-20% rise in base metal prices this year.

Of course, there is still the possibility of a recession, which would dent demand for all metals including copper. BHP Group earlier this month said copper has a "bumpy" path ahead due to demand concerns resulting from a recessionary economic slowdown.

Experts say a sector-wide decline in commodity prices could exacerbate current supply problems by choking off cash flow and chilling investments. It takes at least 10 years to build a new copper mine (20 years in regulation-happy North America), meaning that decisions taken today will determine supply a decade from now.

However, according to an August, 2022 presentation by BloombergNEF, a recession will only delay copper demand, it won't significantly dent consumption projects going into 2040, because so much demand is being "legislated in" through governments' focus on green goals. (The Financial Post)

< 4 days inventory

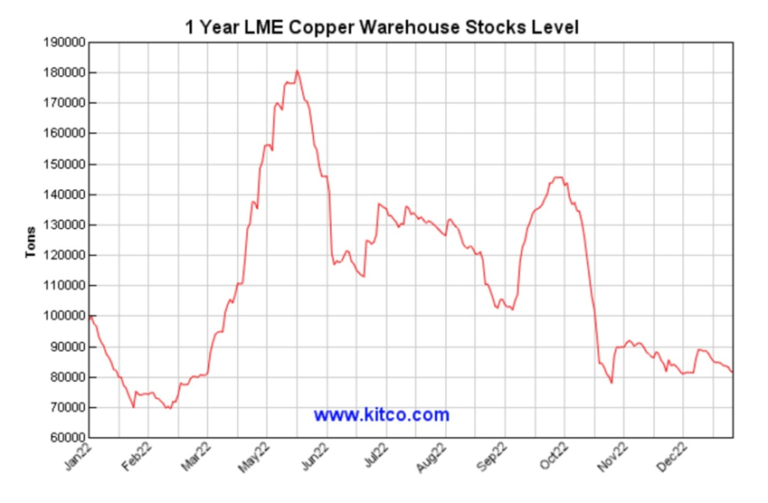

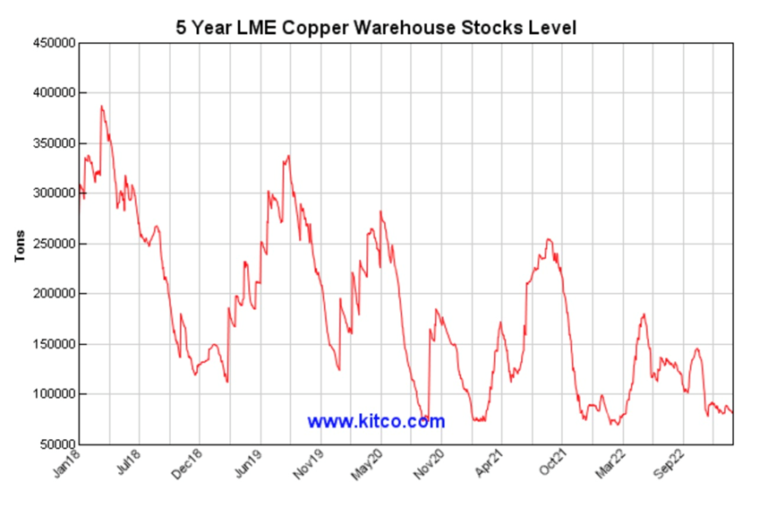

A big part of the copper supply story is dwindling inventories. That, combined with red-hot demand for copper futures, is keeping prices elevated.

Copper inventory right now is less than four days, meaning that combined refined copper stocks in LME, SHFE and bonded Chinese warehouses are only four days worth of global consumption. The indicator is normally measured in weeks.

LME copper warehouse inventories plummeted from 180,000 tons last May, to the current 80,000t. COMEX copper stocks have fallen from 37,000 tons on the 30th of November, to 32,500t.

Source: *****

On Jan. 18, futures exchange operator CME Group said open interest on its copper options reached a record-high 137,574 contracts. Open interest is a measure of investors' participation in a market. It tallies the number of options contracts that are yet to be settled.

CME's monthly copper options posted a 41% increase in trading activity, with open interest of 82,599 contracts at the end of last year, hitting a record high. The Shanghai Futures Exchange's copper contract, launched in 2020, registered year on year growth of 36%, Reuters said.

The physical market for copper, meanwhile, has tightened considerably, with much higher premiums being paid for immediate delivery. On Jan. 20 Reuters wrote,

China's copper buyers face higher costs for the metal this year, buyers and analysts said, after market disruptions from top importer Maike Group's financial woes and production glitches at domestic smelters pushed local premiums to their highest in years.

Premiums paid by copper users in Guandong province surged in the third quarter of last year to 349 yuan per tonne over the futures price, compared to just 91 yuan in the second quarter. In the fourth quarter they were 327 yuan.

For annual supply contracts, Guandong smelters hiked their premium to nearly 250 yuan/t this year, up from 130 yuan in 2022. In the industrial east, some smelters have raised their offers for 2023 copper premiums to 300 yuan a tonne, up from 200 yuan last year, a Shanghai-based traders quoted by Reuters said.

Beyond tight physical markets, dwindling inventories, hot futures trading, and robust demand for copper as China re-opens its economy, resource nationalism in two of the world's most important copper-producing countries — Peru and the DRC — is threatening mine production, and stalling investments in future projects.

Peru protests

Peru, the second-biggest copper producer behind Chile, has been rocked by a series of mining conflicts over the past two years, as communities empowered by leftist ex-President Pedro Castillo, press their demands. Castillo was impeached in December and replaced by Vice President Dina Boluarte.

A fresh wave of protests hit Peru's major operations in early 2022, including Glencore's Antapaccay Mine, Southern Copper's Cuajone and MMG's Las Bambas, the country's fourth-largest copper mine and the world's ninth biggest. The demonstrations threaten to block access to almost $4 billion worth of copper.

As of Jan. 19, Las Bambas hadn't shipped any copper concentrate since Jan. 3, due to security concerns. Glencore's Antapaccay is also facing restrictions, Bloomberg said, adding the two mines together account for nearly 2% of the world's copper output. They also share highway access to ports.

Earlier this month, the Switzerland-based firm said a group of citizens arrived at the site, demanded that the operation be stopped, and that Glencore issue a communique asking for the resignation of President Boluarte. The people then forced their way into mine facilities, stole workers' belongings and set fire to the housing area. A week earlier, activists broke into the water plant and started a fire. A source said the plant provides drinking water for over 6,000 people in nearby communities.

Antapaccay had only been operating with 38% of its workforce due to protests. Following last Friday's attack, Glencore decided to halt operations.

Bad deal for the DRC

While governments in Peru and Chile are pressured by protestors to either shut down mines, or provide citizens a greater share of resource revenues to address inequality, the DRC government in Africa is criticizing China for failing to meet its end of a resource-for-infrastructure bargain struck in 2008.

That year, then-President Joseph Kabila signed an agreement that mandated Chinese companies invest $3.2 billion in a copper-cobalt mine, and another $3 billion in infrastructure funded by the mine's revenue. (China Moly has an 80% stake in the Tenke Fungurume copper-cobalt mine)

But according to current President Felix Tshisekedi, while China receives most of its minerals, the Congo hasn't even released a third of the infrastructure funds, meant for roads and buildings.

"We're happy to be friends with the Chinese, but the contract was badly drawn up, very badly," Tshisekedi said, via Bloomberg. "Today, the Democratic Republic of Congo has derived no benefit from it. There's nothing tangible, no positive impact, I'd say, for our population."

Tshisekedi also shouted down rebels in Eastern Congo, for taking advantage of Congo's resources for their own gain. There, an offensive by the M23 rebel group allegedly backed by neighboring Rwanda, has displaced nearly half a million people.

More than 100 armed groups are active in the region and some of them profit from illegal trade in natural resources, which often transit through neighboring countries, Bloomberg said, quoting Tshisedeki:

"Rwanda has been at the base of instability in Democratic Republic of Congo for 20 years. It's thanks to this instability that it can create mafia networks of illicit exploitation of gold, coltan and other minerals."

Rwanda denies the accusation and blames the instability in Eastern Congo on the security and governance failures of the Congolese government.

Conclusion

The demand pressure about to be exerted on copper producers in the coming years all but guarantees a market imbalance, resulting in copper becoming scarcer, and dearer, with each infrastructure initiative and with each ambitious green initiative rolled out by governments.

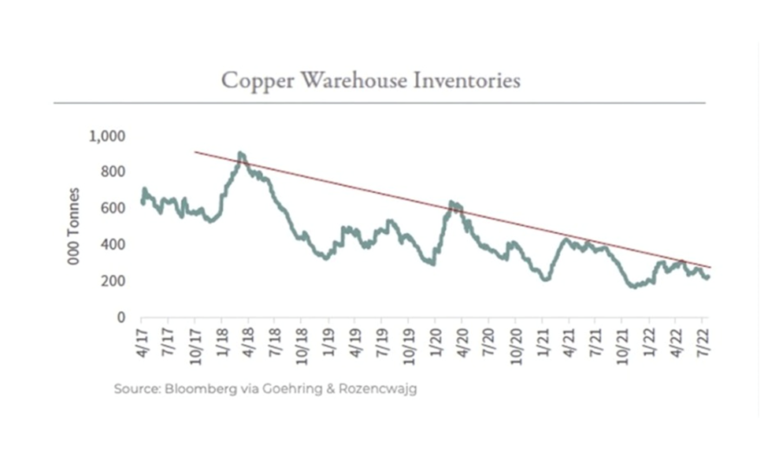

The first problem is dwindling inventories.

Goehring & Rozencwajg, the Wall Street firm, published a chart of copper warehouse inventories showing a four-year down-trend from around April, 2018 to July, 2022. Inventories then rose for about a month, before declining again in October. The long-term trend is down, as the 5-year chart below shows.

Source: *****

Another problem is existing copper mines are running out of ore, and the capital being invested in new mines is far below the level needed.

According to research by S&P Global Market Intelligence, of 224 sizable copper deposits discovered in the past 30 years, only 16 have been found in the last decade.

It takes seven to 10 years, at minimum, to move a copper mine from discovery to production. In regulation-happy jurisdictions like Canada and the US, the time frame is more like 20 years.

The pipeline of copper development projects is the lowest it's been in decades.

Why can't we just mine more copper? Over the past two decades, the big mining companies have approached the problem of dwindling reserves by doing exactly that.

Between 2001 and 2014, 80% of new reserves came from re-classifying what was once waste rock into mineable ore, i.e., lowering the cut-off grade.

The problem is that between lowering their cut-off grades and high-grading (removing all the best ore and leaving the rest) the grade of new reserves each year has steadily declined.

The authors of a 2021 report, Goehring & Rozencwajg, contend that even with prices above $10,000 per tonne, reserves cannot keep growing, specifically at porphyry deposits, where most copper is mined.

Their analysis also suggests that we are quickly approaching the lower limits of cut-off grades, concluding that we are nearing the point where reserves cannot be grown at all. In other words, peak copper.

The industry can no longer re-classify itself out of its problem. Billions and billions of dollars need to be invested in the exploration for, and development of new copper mines.

In sum, the copper industry is in the grips of a structural supply deficit that, combined with inflationary cost pressures and a creeping resource nationalism in some of the world's largest copper producers, is only expected to get worse.

Global shortages of the metal could reach 8 million tonnes by 2032, as soaring demand fails to be matched by new copper mines. The rate of supply increases required, is equivalent to building eight copper mines the size of Escondida, the largest in the world, per year, for the next eight years. That's insane.