Few offshore gas permits in Australian history have caused as much controversy as BPH Energy’s (ASX:BPH) PEP-11 permit off the coast of NSW.

Having been in pre-development for decades – reflecting huge upside potential for domestic east coast gas supply no matter which way you look at it – the permit has filtered in and out of the mainstream spotlight over the years.

Keep domestic energy supply in mind, because that’s what this story is really about – a country that needs more energy security, according to our peak regulator, and a government keen to squash a project that could ill afford doing just that.

But first, let’s do a speedrun through recent history.

PEP-11 most recently popped up on radars across the nation when former Prime Minister Scott Morrison effectively cancelled the permit using powers he gave himself without asking anybody, thereby breaking proper procedure.

Cue BPH Energy taking part in a lawsuit against the Commonwealth; cue an out-of-court settlement where the Government agreed to ‘set aside ‘the refusal. Handy for Canberra.

Last year, that cancellation of the permit was found to be void, vindicating BPH Energy and its enthusiastic shareholders. As of early 2024, however, we haven’t really heard from the appropriate body whether or not the permit will be extended.

How PEP-11 became a villain

As for why generally pro-energy-industry ScoMo cancelled the licence in the first place?

Supposed public opposition against the PEP-11, and a deeply unpopular Prime Minister scrambling for support.

The big objections to PEP-11 in the minds of those against it are twofold: while a strong environmental bent is present in public support for a ban of PEP-11 (seismic testing is loved by the public about as much as fracking.)

However, it should be noted neither of these methods are proposed in the application to vary the work program there’s also development concerns – basically, some just want to keep their ocean views. (Though, no one can see gas drilling rigs in situ for about two months 25km out to sea.)

But whether or not characterisations of public opposition against PEP-11 as framed by those advocating against it are truthfully accurate is up for debate.

BPH Energy chief David Breeze believes that representations of intense opposition against the project have been “confected” by environmentally motivated anti-development spokespeople.

An AFR-led survey run via polling firm Freshwater in September of 2023 found that when asked to select energy preferences, voters supported fresh gas projects as much as they supported wind, around 56%.

Meanwhile, another survey conducted earlier last year in the Hunter Region of NSW – a jurisdiction intimately close to the PEP-11 permit boundary – found that 61% of respondents supported exploring and using more of Australia’s gas reserves. Nearly 40% showed specific support for offshore exploration. Only 10% opposed.

As for the environmental argument, BPH Energy sees questions to be asked on the public statements advocates against the project have made publicly in the past. Those questions have also been raised in submissions the company has made to official inquiries.

In October last year, PEP-11-linked Advent Energy – of which BPH owns a nearly 40% stake – submitted to NSW’s Committee on Environment and Planning that comments from Surfers for Climate spokesperson Belinda Baggs, a once-leading voice against PEP-11, were poorly researched.

Baggs spoke out against PEP-11 by bringing up her experiences surfing a world away off the coast of California, at one point, recalling how she had personally surfed through surface oil slicks the product of offshore oil and gas production.

However, despite the fact that California’s coastline and NSW’s are issues quite literally a world apart, an inherent geological misinterpretation underpins Baggs’s comments. In short: natural oil seeps have been known to occur off the Santa Barbara Channel since 1792—and oil and gas extraction has reduced them, not increased them.

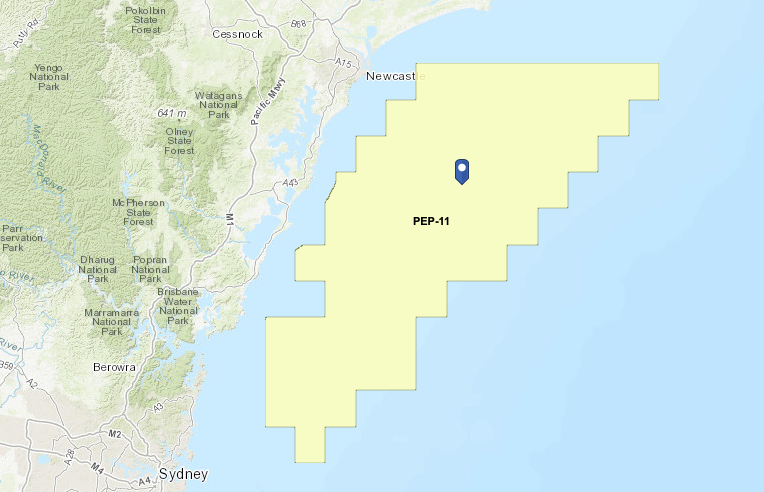

It’s also worth noting that PEP-11 is a huge permit, which has helped to garner support against the project up and down the coast (even though any notion a fleet of offshore rigs would dot the horizon is foolish – and the company has said publicly it only plans activity in northern portion of the permit offshore from the Lower Hunter region.

It’s easier to just look at a picture of the permit boundaries to understand all of this.

ScoMo is part of the past now, but that opposition against PEP-11 isn’t.

And this is why two levels of government are renewing fresh attacks on the permit – most recently the New South Wales state government.

But the man now in charge of Canberra, at least at one point, didn’t exactly mince words either.

Albanese uncharacteristically vague

While Australian lawmakers recently saw a bill from NSW Teal independent Zali Steggal to ban PEP-11 late last year, in the lead up to the most recent Federal election, Anthony Albanese told the press he’s against PEP-11, too.

Strange for the leader of a government with three key members – Albanese himself, federal energy minister Chris Bowen and federal resources minister Madeleine King – all coming out in support of Australia’s gas industry in the recent past.

Especially given that Business NSW and the Energy Users’ Association of Australia (EUAA) have both called on the government to increase gas supply, with Business NSW worried that government policy has become “detached from understanding of gas demand” and the EUAA outright calling for an outright increase in supply through new projects.

Albanese, reeling from the referendum debacle (and still copping heat over tax cuts and planned phase-outs for petroleum cars) has been staying fairly quiet on whether or not this is still the way he feels.

But NSW parliamentarians are making their feelings heard.

In fact, PEP-11 has been the subject of no less than three pieces of proposed legislation in recent history.

Most recently, the Environmental Planning and Assessment Amendment (Sea Bed Mining and Exploration) Bill 2024.

Labor, Liberal, and independent representatives have all taken pot-shots at the PEP-11 permit, making it a bona fide underdog in the Australian energy landscape.

So will the Federal government put the final nail in the coffin for good, or won’t they? Obviously, I don’t have the ability to read the Prime Minister’s mind (nor would I want to.)

But at the moment, the real threat to the project is coming from state lawmakers in NSW – even though the project is not in State waters and will be subject Federal regulation, not State.

Hang on. Aren’t we running out of gas?

And therein lies the big question mark in the minds of project proponents, as well as the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO).

In its recent publication 2023 Electricity Statement of Opportunities (ESOO), AEMO outlined its view of the next ten years for Australia’s National Electricity Market (NEM.) That view wasn’t one free of concern.

In short, AEMO is worried about gas supply shortfalls throwing a massive spanner into the operations of the NEM – something highlighted in the NSW Legislative Assembly Committee on Environment and Planning.

In fact, AEMO’S 2023 ESOO uses the word “gas” no less than 75 times.

“The impact of potential coal, gas and diesel fuel shortfalls has been identified as a material risk to the reliability of the NEM,” the regulator wrote in August last year.

“The ongoing availability of coal, gas and distillate fuels, and effective management of their supply chains, will be critical to the reliability of the NEM.”

The mention of supply chains brings up a different point to make, and not just because AEMO sees Australian power demand – and thus reliance on the NEM – picking up into the 2030’s.

(The regulator actually revised upwards its demand outlook in the 2023 ESOO).

More to the point, in the last two years, Australia has watched Europe suffer through brutal winters after its energy security was threatened by a geopolitics-borne supply clampdown from Russia.

The Dutch natural gas futures contract decided at the port of Rotterdam hit record all-time-highs, driving a wave of insolvencies across the Eurozone (and the UK.)

To say that the national power grid and a country’s economy are linked is an overwhelming understatement.

Anybody who’s ever had their fridge break down will happily tell you the quality of life we enjoy is sustained by a hidden ecosystem of copper wires watching over all of us with loving grace.

At the same time, ongoing tension with China continues to push Australia into a scramble for realisation of domestic critical minerals supply. Anthony Albanese in February of 2024 said that our economic future lies with Southeast Asia – a fairly sensational claim that was perhaps overlooked.

At any rate, it is against this backdrop the importance of domestic resource supply security has become something of a household talking point (at least, it has in my house.)

And with AEMO flagging a direct threat to the proper operation of Australia’s power grids posed by the possibility of gas supply shortfalls – any decision to ban PEP-11 can be fairly called a risky political move.

Are the votes worth it?

How BPH Energy sees it

Worth noting before we go on is that BPH Energy isn’t technically the sole operator behind the permit, but the company’s ultimate value proposition is tied up in its 35.8% stake in Advent Energy; a company that largely owns the permit through a subsidiary with an 85% stake.

ASX-lister Bounty Oil and Gas (ASX:BUY) holds the remaining 15%.

It’s admittedly even more complex than that, but that’s the need-to-know of the ownership structure. Big offshore projects take a lot to get right.

The first big thing BPH Energy has always stressed is that the Bass Strait region offshore Victoria – which has produced around 6 trillion cubic feet of gas over the last 60 years – is in decline.

One well already sits within the PEP-11 permit, drilled by the permit owners – New Seaclem-1, sunk all the way back in 2010.

In the last half-decade, BPH Energy has been spearheading the pre-drilling development of a second well called Seablue-1, which remains – along with the entire permit – in limbo.

At the same time the Bass Strait is in rapid decline and AEMO has all but said gas supply shortfalls threaten the Australian grid, and thus, its economy.

In this light, the palpable frustrations of BPH Energy shareholders become clearer.

And those frustrations are exacerbated by other undeniable facts-of-life which both Canberra and the NSW Government wholesale appear to have failed to consider.

Among them: Australia’s population is growing, guaranteeing AEMO’s demand projections are likely to ring true, the ACCC published a production cost at A$8/gigajoule (GJ), and the Sydney Basin could potentially be used for Carbon Capture – which would assist Canberra to reach UN-linked climate targets.

At $8/GJ, this would also help guarantee that Australia avoids a situation it saw in the COVID years when the Australian gas price hit $28.40/GJ.

That fiasco triggered Canberra into introducing a $12/GJ price cap – and if Advent can do it for even cheaper than that, all things in order per its operational plans.

And yet, NSW lawmakers remain unafraid to fire shots at PEP-11 for what is clearly vote-scoring, while Canberra – through Albanese – has previously hinted it’s not a fan either.

If the government wakes up and is forced by blackouts to address the situation this country is in, the company has an objective of reaching production only 2 years after a commercial deposit is found as opposed to the usual half-decade timeline most offshore projects must endure.

BPH Energy’s David Breeze confirmed to The Market Online that the company is “moving to a drill ready status” with negotiations related to rig hire already underway to enable the company to move quickly once regulatory approvals obtained.

Breeze also pointed to Andrew Forrest’s recent decision to scrap his ambitious vision of an LNG import terminal for Australia’s east coast. In the markets view, it simply can’t be done – – as there is no spare capacity from the NW Coast, itself facing a decline in the near term and spare capacity of LNG from elsewhere, should such exist, are likely to be prohibitively expensive, given the forecasted demand for LNG across Asia. and Canberra’s wasting time investigating that possibility.

The Seablue-1 well is also to be located less than 30km from an existing gas line owned by private Australian utility giant Jemena, tied to the Colongra Power Station in NSW, located 35km from Newcastle as the crow flies.

It’s not like the assets aren’t there to quickly make PEP-11 gas supply a reality for the Australian consumer.

For now, PEP-11 remains in limbo – and its cancellation haunts the minds of our electricity regulator, relevant shareholders, and those who care about the Australian economy.

Its cancellation also threatens millions of dollars of capital already sunk into the development, which for all intents and purposes, appears to be something we’re going to need regardless of renewables, given the fact we’ve failed to act quickly enough to actually make lofty green ambitions work.

Australia needs gas – and the government needs to see that sooner rather than later.