Why is Burkina Faso important to study?

- Burkina Faso may be “one-year-ahead” of where Niger is today. In September last year, Burkina Faso experienced its own coup, bringing to power a 34-year old army captain and geology graduate, Ibrahim Traoré.

In January, Traoré terminated military agreements with France dating back to 1961 and gave Paris four weeks to withdraw several hundred of its special forces that were stationed in the country. France complied.

Similarly in Niger, on August 3 and within a week of seizing power, the military junta announced the cancellation of defense and security arrangements with France stretching back to 1977. France has between 1,000-1,500 troops stationed in Niger. However, unlike its response in Burkina Faso, Paris has refused to recognize the cancellation of its military agreements with Niger.

- The French withdrawal from Burkina Faso paved the way for Russia, and Wagner mercenaries, to begin filling the vacuum. In a rare interview in May, Traoré described Russia as a “strategic ally.”

A civic leader aligned with Traoré hinted at the growing role of Wagner by telling Associated Press:

We asked the Russian government because of the bilateral collaboration between Burkina and Russia, that they send us people to train our men.

Indeed, a week before French soldiers left Burkina Faso in February, the Burkinabè authorities issued a statement saying it had “commandeered” 200 kilograms of gold from a mine operated by British multinational Endeavour Mining, for “public necessity.”

The timing of this statement could, of course, be a coincidence. However, it is possible, although not provable, that the gold was used by the government to pay Wagner for providing security and fighting Islamic extremists.

In any case, these events in Burkina Faso highlight how:

(i) Wagner mercenaries were able to extend their influence following the coup at the expense of French forces and

(ii) Western multinationals with mining interests in Burkina Faso may in the future be faced with selling more gold to the government that in turn is then used to pay for Wagner. This could complicate a mining company’s investor relations.

- There appears to be a degree of political alignment between the military juntas of Burkina Faso and Niger. After all, Burkina Faso has stated that any intervention by ECOWAS in Niger will be seen as a “declaration of war” on it as well. On August 8, with Malian and Burkinabè officials in Niger as a show of support, a Malian spokesman alluded to the alignment among the military juntas of the three countries when he said:

I would like to remind you that Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger have been dealing for over 10 years with the negative socioeconomic, security, political and humanitarian consequences of NATO’s hazardous adventure in Libya.

Thus, there appears to be a convergence of views among the junta stretching back at least a decade. Indeed, there is a growing possibility that Niger will follow a similar path to Burkina Faso as outlined above.

Therefore, by understanding the motivations behind the Burkinabè leader, Ibrahim Traoré, we may be able to infer what the inner-motivations of the Nigerien junta are and what decisions they may take going forwards.

To do this, we need to appreciate the importance of Thomas Sankara in the Burkinabè political consciousness and, critically, in Traoré’s world view.

***

Thomas Sankara came to power in Burkina Faso in 1983 as a 33-year old army captain, almost an identical profile to Traoré. In the West, Sankara was nothing more than a Marxist-Leninist revolutionary that riled against Western commercial interests and imperialism. However, to many in Africa, indeed the broader Global South, Sankara was a nationalist and a pan-Africanist who tried to chart a course of non-alignment during the final days of the Cold War.

Sankara was also seen by many across Africa as a worthy successor to the ideals and ambitions embodied in Patrice Lumumba, the first democratically-elected Prime Minister of Congo. Lumumba, who was murdered in a Western-orchestrated coup in January 1961 and had his body dissolved in sulphuric acid, was replaced by Joseph Mobutu, a U.S.-funded autocrat. Mobutu would rule Congo (known as Zaire between 1971-1997) with an iron fist until his death in 1997.

In 1984, Sankara renamed the country “Burkina Faso,” meaning “upright people of the fatherland” in the local Burkinabè languages.

Previously, the country had been called the French Upper Volta since 1919.

Sankara’s vision for Burkina Faso included:

- Advancing public health through mass vaccination programmes for children.

- Leading an anti-corruption drive.

- Lowering the illiteracy rate from 73% to 13%.

- Instigating the Great Green Wall project to increase the amount of arable land across the Sahel, thus improving food security.

- Promoting women’s freedoms (he outlawed polygamy and FGM (female genital mutilation), and appointed women to senior roles in government).

Sankara aimed to reduce his country’s reliance on food imports. Following the Volcker shock starting in October 1979, food and energy imports for countries like Burkina Faso became even more expensive.

In Sankara’s own words, he wanted to put Burkina Faso on a path of “non-conformity” and to have the “the courage to turn [their] back on the old formulas.”

However, despite these efforts towards domestic socio-economic development, Sankara was becoming a growing nuisance to Paris.

- In November 1983, Burkina Faso was elected as a Non-Permanent Member of the UN Security Council for two years. In 1984, Sankara supported a nationalist movement in New Caledonia, a French territory in the South Pacific. Sankara used his vote to ensure the territory was included on the UN’s decolonization commission. This action incensed Paris.

- Sankara boycotted the annual Franco-African summits.

- Paris was concerned that Sankara was growing too close to Ghaddafi in Libya. In 1983-84, France was engaged in a proxy war with Libya over territories in northern Chad.

- Then there was an evening that has gone down in infamy in the history of Franco-African relations.

In November 1986, President Mitterrand arrived in Burkina Faso for a state visit. During the gala dinner—in a room filled with TV cameras and broadcast live—Sankara launched into an all-out assault on French colonialism, imperialism, duplicity and support for the apartheid regime in South Africa (see an extract here).

Mitterrand, on the receiving end of an oratory performance par excellence, looked ashen, humiliated and taken off-guard. Sankara’s speech was so impactful that when he finished and Mitterrand took to the stage, the French President ditched his pre-prepared speech and addressed Sankara’s points “on-the-fly.”

The image of a young African leader—symbolizing a rising Africa—publicly humiliating a stiff, white, septuagenarian leader of a former colonial power was in plain sight.

Sankara’s biographer, Bruno Jaffré, later noted that:

[Some people thought Sankara]had signed his death warrant by arresting François Mitterrand on the evening of November 17, 1986.

- Sankara also campaigned against what he perceived as economic colonialism and debt enslavement to the West. In July 1987, at a summit held at the Organisation of African Unity in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Sankara gave a powerful speech called "A United Front Against Debt" where he called on other African countries to refuse debt repayments to former colonial powers.

Sankara said:

Debt’s origins come from colonialism’s origins. Those who lend us money are those who colonized us.…. We had no connections with this debt. Therefore we cannot pay for it.

Debt is neo-colonialism, in which colonizers have transformed themselves into “technical assistants.” We should rather say “technical assassins.”

Under its current form, controlled and dominated by imperialism, debt is a skillfully managed reconquest of Africa, intended to subjugate its growth and development through foreign rules.

Thus, each one of us becomes the financial slave,which is to say a true slave, of those who had been treacherous enough to put money in our countries with obligations for us to repay.

We cannot repay because we don’t have any means to do so.

We cannot pay because we are not responsible for this debt.

We cannot repay but the others owe us what the greatest wealth could never repay, that is blood debt. Our blood had flowed.

In October 1987, three months after this speech, Sankara was assassinated with his mutilated body dumped in an unmarked grave.

In April 2021, a military court in Burkina Faso found Blaise Compaoré, a former ally of Sankara, guilty in absentia for the assassination. It is unclear to what degree, if any, Paris was involved.

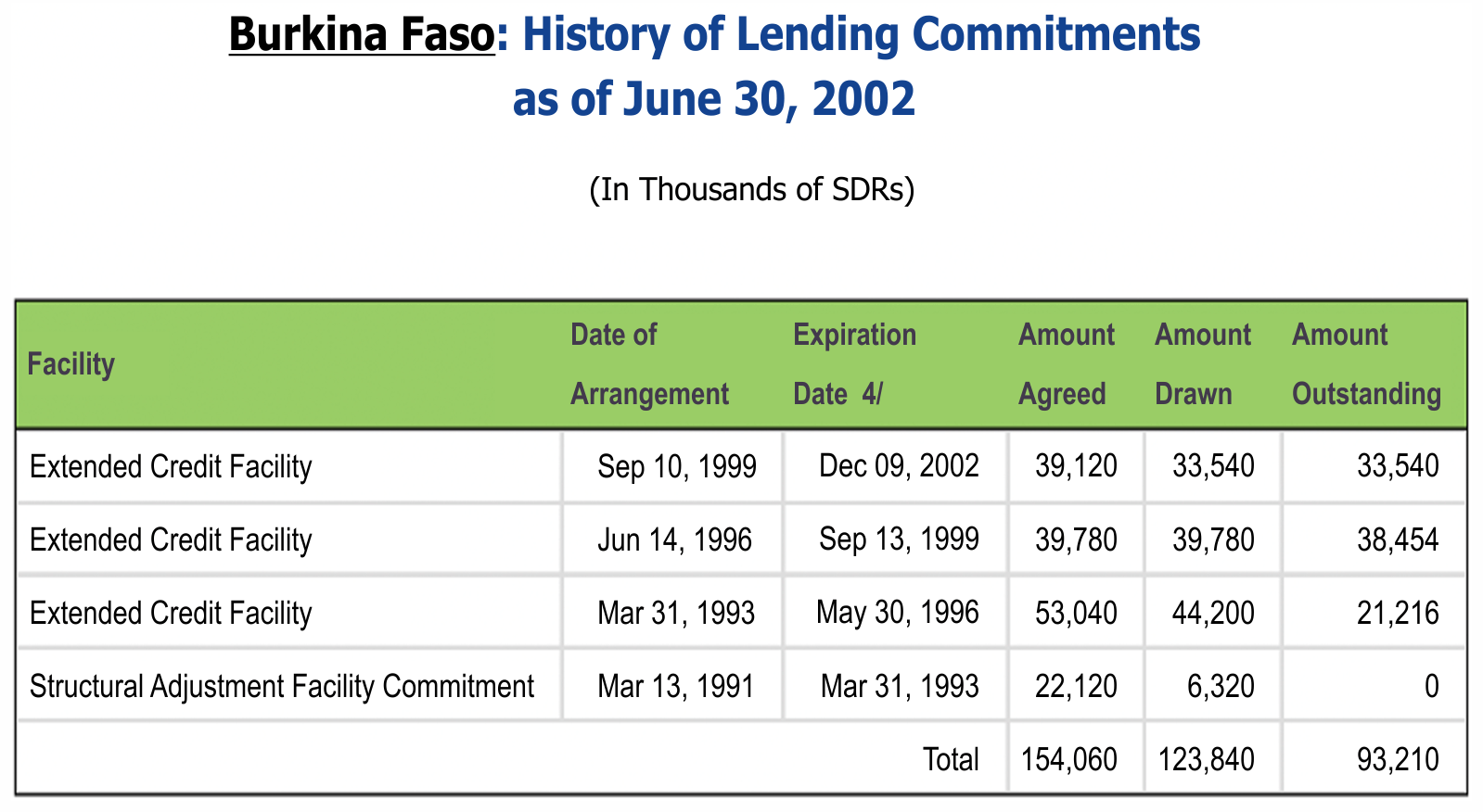

However, what is clear, is that during Compaoré’s 27-year rule until 2014, he became increasingly aligned with Washington and Paris, followed through with four structural adjustment programmes with the IMF and accepted a series of loans from the World Bank.

Source: IMF

Source: IMF

Why is this important?

First,regardless of whether it is justified, the echoes of Lumumba, Sankara—and even Mandela during his 27 years of incarceration—ring in the military juntas’ ears when Washington and Paris today call for the “restoration of the democratic order” in Niger.

Second, Ibrahim Traoré, the leader of Burkina Faso, appears to be modeling himself on Sankara.

- Traoré’s first act as leader was to visit the Thomas Sankara memorial in the capital Ouagadougou. The theme of the 35th anniversary of Sankara’s assassination was “Passing the torch of the revolution to the youth.”

- In a speech at the Russian-African summit last month, Traoré evoked similar terminology as Sankara and appeared to reference him.

Traoré said:

In Burkina Faso, we have been confronted for more than eight years with the most barbaric, most violent form of neo-colonialism and imperialism.

Slavery continues to impose itself on us.

Our predecessors taught us one thing: the slave who cannot carry out his own revolt doesn’t deserve to be pitied….

We African heads of state must stop behaving like puppets who dance every time the imperialists pull the string.

- After Sankara’s body was exhumed in 2015, Traoré organized in February for the former leader to be given a state funeral.

- Traoré has appointed a former ally of Sankara as his Prime Minister. In his 2023 New Year speech, Traoré tasked the 68-year old veteran to drive the “refoundation of the nation.”

What are the implications?

If Traoré is modeling himself on Sankara while also supporting the new junta in Niger, we can infer that the Nigerien putschists—as well as the junta in Mali—may also be sympathetic to the ideas of Sankara.

- Today, the geopolitical map is arguably more favorable for Traoré than it was for Sankara in the 1980s.

- Traoré has regional allies—Guinea, Mali and Niger—as well as a close relationship with Putin. For example, if these countries wanted to coordinate export bans on uranium and gold, the effects in Western markets would be felt more acutely. In addition, the appetite for Western military intervention, unlike in previous decades, is likely to be diminished.

- In the 1980s the BRICS did not even exist. Today, the hegemony of the dollar—and the geopolitical leverage it has granted Washington, the IMF and the World Bank by weaponizing the financial system—is being challenged by a new, emerging, parallel monetary architecture centered around the BRICS.

There are some indications that the BRICS may unveil further details about an intra-bloc trade currency anchored to gold at the organization’s annual summit later this month. Over time, the BRICS may develop a cross-border payment system that is protected from Western leverage.

As it currently stands, the BRICS comprise over 40% of the global population. According to the IMF, for 2023, the BRICS share of global GDP (on a PPP basis) is projected to be 32.1%, versus 29.9% for the G7.

By 2028, the G7 is expected to make up 27.8% of the global economy, while the BRICS will make up 33.6%.

Critically, the BRICS share of global GDP does not include the list of new members (over 40 countries at the latest count) that are seeking to join the organization.

- With the potential of an alternative architecture emerging—along with alternative lending institutions such as the New Development Bank (NDB)—what is stopping heavily indebted nations, that have decided to align with non-Western powers, from rejecting IMF “diktats,” reneging on dollar-denominated debts and joining a new, alternative system with a clean slate?

The most dangerous opponent is the one who has nothing to lose.

Indeed, in an interview on April 15 with Chinese network CGTN, Dilma Rouseff, the head of the NDB, said:

It is very important to me that the NDB of the BRICS acts as a tool to support the development priorities of the BRICS and other developing countries.

- In the Emerging Multipolar World Order:

Are Western creditors prepared if indebted nations default on their fiat debts in the knowledge that a new, monetary system backed by commodities—outside of the IMF and credit rating agencies—may be emerging?

As an old adage goes: if you owe $10,000 it’s your problem; if you owe $100 million it’s the bank’s problem; if you owe $10 billion it’s the government’s problem.

***

!

$2.17

!

$2.17

(20min delay)

(20min delay)