Flaw #1: Out-scoping costs

Sunk costs before 2030 in GenCost

CSIRO’s GenCost report outscopes storage and transmission project costs incurred before 2030, effectively treating them as a sunk cost,[17] which makes variable renewables (i.e. wind and solar) seem far cheaper than coal, gas and nuclear, even at high levels of penetration.[18]

GenCost is primarily concerned with costs to investors for different new-build generation and storage technologies at a particular time, not whole-of-system costs.[19] The key data GenCost uses to compare these technologies are capital costs and the Levelised Cost of Electricity (LCOE) — the average price of electricity an investor would need to receive over the life of their investment to recover both capital and operating costs.[20] However, the 2030 LCOE analysis treats pre-2030 transmission and storage projects as

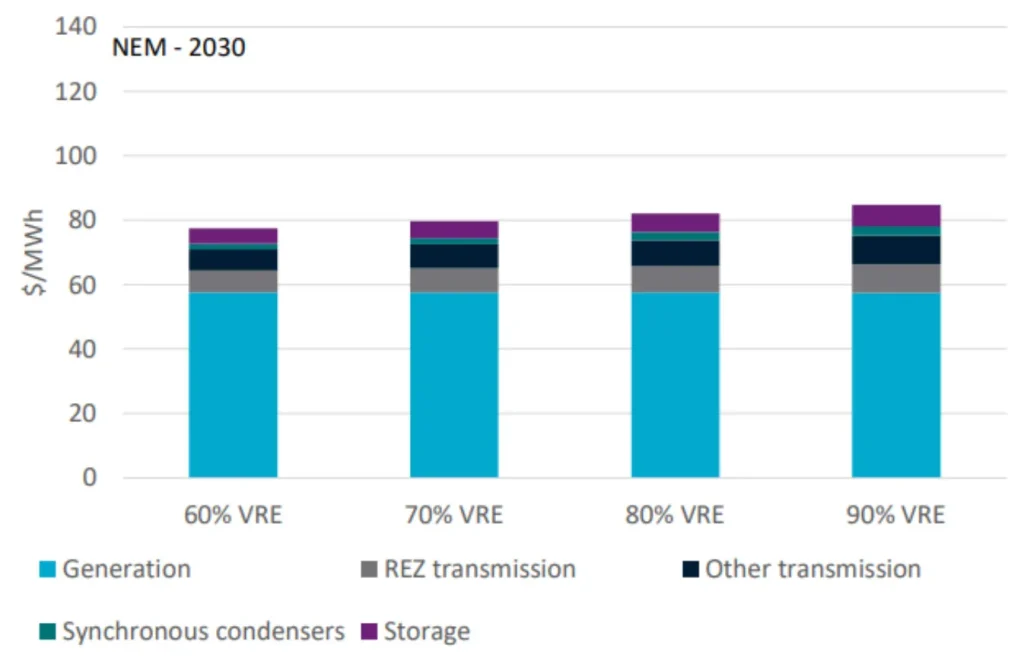

‘free’,[21] making variable renewables appear to have relatively low integration costs compared to the costs of generation (see Figure 1).[22]

Figure 1. Levelised costs of achieving 60%, 70%, 80% and 90% annual variable renewable energy shares in the National Electricity Market NEM in 2030.

As renewables usage increases, the GenCost model forcibly retires coal plants.[23] This should result in transmission and storage costs dramatically increasing with higher usage, as reduced reliable baseload power necessitates renewable energy being transported further and stored for longer.[24] Although this sharp increase is commonly found in other studies estimating costs for increasing renewables penetration,[25] GenCost counter-intuitively depicts a negligible increase in integration costs from 60 to 90% variable renewables (Figure 1). If the costs of pre-2030 transmission and storage projects were fully included, the increase would likely have been much greater.

In response to concerns about the exclusion of pre-2030 integration costs being raised by stakeholders during previous GenCost report consultations, CSIRO has attempted to estimate these costs in the Draft 2023-24 report.[26] These 2023 integration costs include two gas plants, Snowy Hydro 2.0 and other major storage projects[27] and 11 transmission projects flagged by AEMO’s Integrated System Plan as being needed by 2030.[28] CSIRO “abstracts from reality” and assumes these projects can be completed immediately so that they can be included in the 2023 LCOE, [29] without accelerating the depreciation of these assets.[30] This means the 2023 analysis has essentially assumed the costs of pre-2030 transmission and storage projects can be fully paid off in 7 years so that they are completely free for the 2030 analysis, without any additional costs arising from this compressed timeline. This does not reflect reality, neither showing only the costs to investors nor the full costs a consumer would realistically face.

Additionally, no attempt was made to calculate what proportion of integration costs arising from these projects is necessary at each share of variable renewables — instead all costs are included regardless of renewables share.[31] This results in the pattern of decreasing costs with increasing penetration of renewables (Figure 2), because the cost of the pre-2030 storage and transmission projects can be spread over more variable renewable energy generation the greater the variable renewables share.[32] In reality, fewer transmission and storage projects would be needed with lower usage of renewables. Rather than clarifying the integration costs of renewables, this analysis only serves to mislead readers into thinking integration costs will become cheaper as more renewables are added to the system.

- Forums

- Political Debate

- Six fundamental flaws underpinning the energy transition - Independent Report