From Long Waves

International Perspective, by Marshall Auerback

Korea’s Election Results: Another Decisive Turn Against Washington

December 24, 2002

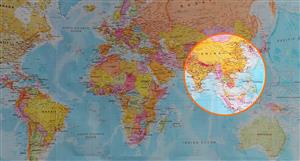

Pentagon strategist Franklin “Chuck” Spinney has recently noted that “the flower of popular sympathy and goodwill toward the United States that blossomed in the immediate aftermath of September 11 has now wilted.” Since April, a growing number of public opinion polls and anecdotal news reports have suggested that people all over the world feel alienated by the actions of the United States, including those actions flowing out of the country’s evolving military strategy for fighting the war on terror. To illustrate his argument, Spinney highlights the Pew Global Attitudes Project, which recently published the most extensive world-wide poll to date (of more than 38,000 people). Entitled "What the World Thinks," the Pew survey painted a horrifying portrait of anti-American sentiment spreading around the world like a contagious virus. Now this is being manifested even amongst America’s democratic allies, notably those in Asia.

Roh Moo-hyun's victory over his conservative opponent last week in the Republic of Korea’s (ROK) presidential elections was a narrow one, but it seems consistent with the results tabulated by the Pew Global Attitudes Project. The election result is vast in its implications for Seoul, the northeast Asian region, and trans-Pacific relations with the U.S. For the first time a country outside America has had the opportunity, not in polls, but through a proper democratic election, to express its genuine feelings about the current drift of American foreign policy, which impacts particularly on the Korean peninsula. The conflicting approaches to the problem of North Korea adopted by the respective candidates was a major electoral issue in the ROK, particularly in light of the most recent flair up of tensions between Pyongyang and Washington.

The Korean electorate’s conspicuous dismissal of President Bush’s hard-line stance against North Korea (through its rejection of the pro-American opposition candidate, Lee Hoi Chang) marks another fracture in the post-war alliances that have governed America’s relations with the outside world, splits which have surely accelerated since the region’s economic crisis of 1997/98. Regardless of what one thinks about the merits of this resurgent pan-Asian nationalism, its conspicuous rise over the past 5 years ultimately has implications for Asia’s historic satellite economic relationship with America, which flows from these longstanding Cold War structures. After all, three-quarters of the world’s reserves are still held in U.S. dollars, and Asia remains by far the largest repository of these deposits. The extent to which these countries move away from the American security umbrella might also affect their longstanding proclivity to hold their foreign exchange reserves in virtually nothing but greenbacks.

Millennium Democrat Party candidate Roh Moo-hyun won a close race and most major papers in Korea read the results as a foreshadowing of strained relations between the United States and the ROK. Roh (whose name is pronounced "No") has said in recent days that South Korea should have stronger dialogue with North Korea and that the South should assert its independence, making sure the U.S. doesn't go to war with the North. To be sure, in speeches subsequent to his electoral victory, Roh has made the requisite calls to maintain strong ties with the U.S., but as the honorary senior research fellow in sociology and modern Korea at Leeds University, Aidan Foster-Carter, has noted, “Mr Roh breaks the mould of traditional politics in Seoul. A human rights lawyer from a poor, farming family, he never went to university. What is more, he has never visited the U.S., South Korea’s principal ally and protector. He appears proud of both these accomplishments.”

By contrast, Roh’s main opponent, Lee Hoi Chang favoured a hard line toward Pyongyang and a relationship with Washington that was straight out of Cold War tradition. A former Prime Minister, he used Pyongyang’s disclosure of a nuclear weapons program to repudiate President Kim Dae Jung’s “sunshine policy” and to fall into line with a more confrontational approach advocated by Washington. One had no sense that Lee shared the views of Kim and Roh on the need to rebalance U.S.-Korean ties to reflect Korea's emergence as a regional power and the realties of a new era. Lee was also softer than Roh on economic reform and entertains close ties to the chaebol, or conglomerates, that long towered over the Korean economy.

Roh's victory confirms Seoul's careful diplomatic approach to North Korea even as this strategy has come under considerable pressure from the U.S. The only thing Roh would change about Kim's “sunshine policy,” the new president said during his campaign, is its name, (although Pyongyang’s latest actions have certainly complicated the prospects for immediate re-engagement between North and South). Despite heightened tensions, this repudiation of Washington’s increasingly hard-line posture should occur in South Korea is striking, given that the very existence of the ROK is largely a function of the U.S. helping to man the most heavily fortified military dividing line in the world – in itself a product of the Cold War.

But the benefits of a demilitarized zone across the 38th parallel of the Korean peninsula have not flowed uniquely to the South; it has served America’s interests as well. For much of the Cold War period, the very existence of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) has induced most of the capitalist countries in the region to “communicate” with the communist countries through the American military, with the smaller countries sustained by American aid grants (which constituted five-sixths of South Korea’s imports in the late 1950s). As Korean scholar Bruce Cumings has observed:

“The long-term result of this history from 1945-1953 may be summarized as follows: the capitalist countries of the region tended to communicate with each other through the United States, a vertical regime solidified through bilateral defense treaties (with Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and the Philippines) and conducted by a State Department that towered over the foreign ministries of these four countries. All became semi-sovereign states, deeply penetrated by American military structures (operational control of the South Korean armed forces, U.S. Seventh Fleet patrolling of the Taiwan Strait, defense dependencies for all four countries, military bases on all their territory) and incapable of independent foreign policy or defense initiatives. Horizontal contact between South Korea and North Korea or China was non-existent, but was very much attenuated with Japan as well.”- (“Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History”, W.W. Norton & Company, 1997).

This arrangement enabled the U.S. to retain unparalleled influence in the region for virtually the entire Cold War. As President of the Japan Policy Research Institute, Chalmers Johnson, has observed, there was far more symmetry between the post-war policies of the former Soviet Union and the United States than most Americans are prepared to recognise. Just as Eastern European’s dreary leaders faithfully followed every order they ever received from Moscow, so too, each and every Japanese, Korean or ASEAN leader has until recently reflexively acquiesced to Washington’s policies.

But there was a key difference between American and earlier imperial traditions: as the international relations theorist Ronald Steel has observed, “Unlike Rome, we [America] have not exploited our empire. On the contrary, our empire has exploited us, making enormous drains on our resources and energies.” Johnson makes the point that an analogous situation literally wrecked the former USSR: “While fighting a losing war in Afghanistan and competing with the United States to develop ever more advanced ‘strategic weaponry,’ it could no longer withstand pent-up desires in Eastern Europe for independence.” That same pent-up desire for greater independence is increasingly manifesting itself in Asia. A resurgent nationalism in the region might complicate America’s war on terrorism if it persists with the robustly unilateralist approach embodied in the so-called Bush defence doctrine and render more problematic its persistent reliance on Asian capital flows to sustain economic growth in spite of growing financial imbalances.

For a generation, China was conspicuously excluded from this post-war system of alliances, but this has now changed with China’s embrace of free market reforms and its corresponding growth as an economic locus for the region. Similarly with Russia and Japan, where Prime Minister Koizumi has also pointedly insisted that his country would continue its rapprochement with the North Koreans. Other Asian countries – Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia in particular – have taken comparably robust independent lines. And in the Republic of Korea itself, the electorate seems to have viewed Lee Hoi Chang’s assertion that Seoul should line up with Washington to isolate the North as an increasingly anachronistic Cold War philosophy unsuited to the region’s current needs. How long before this reassessment takes on broader considerations of the economic ties that have mirrored these strategic relations?

The most fundamental consequence of Roh's political triumph lies in Korea's relations with the U.S., which will be tested as the crisis over North Korea’s nuclear weaponry intensifies. How the new administration in Korea responds to this intensifying pressure will determine the degree to which the Washington/Seoul relationship is destined to lose its teacher-pupil aspect in favour of more balanced ties. Seoul under Kim has made itself a regional power and is likely to insist under Roh that it is acknowledged as such, rather than being viewed as an American economic protectorate.

But in truth the seeds for this changing relationship were planted well before the latest election. If the Cold War in Europe ended in Europe in 1989, the watershed event in East Asia’s changing relationship with America really dates back to Asia’s financial crisis of 1997/98, of which Korea was a major casualty. Although many in the West persist in seeing the source of that economic turmoil as overinvestment, corruption, and the reluctance to embrace liberal market reforms, there was one conspicuous special financial feature that clearly exacerbated the crisis. Greedy foreign lenders lent to Asia’s highly indebted firms because they wanted to join in what was thought to be part of the great Asian growth story. Based on their Western prudential limits and guidelines, these western institutions should never have lent to Korean firms who were leveraged at least four to one, but they did. When the environment soured, they looked at these companies for the first time in terms of their prudential limits and guidelines and decided they wanted out.

This is in contrast to other debt crises in the emerging world. When banks lent to Brazilian or Argentine firms in the 1970s, for example, these firms had conservative balance sheets. When balance of payment crises afflicted these countries, the banks were nonetheless able to justify their exposure on the basis of corporate credit worthiness criteria even if country worthiness criteria were not met, and they rolled over their loans as a consequence. In the Korean context, indeed, in all of Asia, these highly indebted firms’ situation was made worse by the impact of currency devaluation on the external debt, and the toxic financial derivatives packages sold these companies by Wall Street investment banks.

We have no doubt that, to an increasing degree, international mobile capital is driven by American “short-termism”. Unlike direct investment, it is interested in short-term trends, not long run prospective returns based on economic fundamentals. It seeks to ride speculative trends generated by market misconceptions and the emotion of market participants. It posits adaptive, not forward-looking rational, expectations by market participants and employs technical analyses to identify and follow short-term price patterns. In a modern world of instantly accessible information, and low transaction costs, it is not surprising that such speculative forces have become increasingly destabilising. And they were highly destabilising in Asia. American policy makers’ insensitive triumphalism during this period helped to exacerbate the growing anti-Americanism that was a significant factor in Roh’s recent victory.

In fact, the electoral responses to the 1997 crisis has been fairly consistent throughout the region – the election of Thaksin in Thailand, Megawati in Indonesia, the continuing dominance of Mahathir Mohammed in Malaysia, and now, Roh Moon-hyun’s recent triumph in Korea – been marked by greater nationalism, populism and increasingly Asia-centric policy making. There has been a tendency to revert to Asia’s old model of “Alliance capitalism” and less ready acceptance of the neo-liberal market structures that predominate in the U.S. Additionally, Asian policy makers are beginning to note how odd it is that today’s global financial architecture continues to favour the debtor nations of the West, as opposed to the regional savings bloc of Asia.

The aggregate net creditor position of Asia dwarfs their respective indebtedness. Korea, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia, for example, have a gross external debt of something more than $400 billion. Much of this is multilateral and bilateral debt and suppliers credits with long-term maturities and favourable terms that should not be refinanced. Perhaps less than $300 billion is left, and surely not all external creditors would wish to be displaced. The actual volume of funds needed to totally stabilize the funding of the affected nations must have been $100 to $200 billion at most at the peak of the crisis of 1997/98 and is probably substantially lower today, as Asia’s current account surpluses continue to mount.

As things stand right now, global investors are extracting huge risk premiums from the entire emerging markets universe as a quid pro quo for the provision of their capital. Asia has not remained immune from this process. This seems manifestly perverse to us. All of the nations of Asia continue to run large current account surpluses, the proceeds of which are funnelled back into the US Treasury market, where the savers obtain a yield of around 4 per cent or less, in a country which is now the world’s largest debtor nation and suffering from historically unprecedented private financial sector deficits. By contrast, to borrow even leading companies such as Samsung are forced to pay several hundred basis points above the yield of Treasuries. The Western investor or banker is extracting a wholly unmerited premium, whilst the US is in effect trading on its reserve currency and safe haven status to subsidise its over-consumption and perpetuate the country’s growing financial imbalances. This readily explains, amongst other things, the Treasury’s continued violent opposition to an Asian Monetary Fund.

But America’s role as the world’s lone superpower and its corresponding dominance over the major international economic institutions, the IMF, World Bank, and World Trade Organisation, are likely to be complicated by the nature of the harvest the country has reaped through actions undertaken in the recent past. The wealth of Asia has fundamentally altered the world balance of power. The Asians themselves are increasingly asking whether the world’s largest creditor bloc should continue to act from such a position of supplicant, despite this enormous accumulation of reserves. Korea’s latest election results seem to be part of a collective Asian response to this question. Notwithstanding that a reservoir of goodwill toward the U.S. still exists (albeit one viewed as a rapidly depleting resource), the answer is becoming an increasingly unequivocal “No”. A militarization of grand strategy in Asia is an extremely dangerous phenomenon. This risk becomes especially dangerous to the U.S. if the Asian creditors who help to fund this strategy (through their persistent financing of the American current account deficit) ultimately decide that their interests are better served by adopting a different course of action.

- Forums

- ASX - General

- asia to flex its muscles soon?

From Long WavesInternational Perspective, by Marshall Auerback...

Featured News

Featured News

NEWS

Antler Copper Project hits major permitting milestone – air quality permit advances to final review