If the recent sell down in POG is causing IGR holders to sell off their shares, this article shows that the central banks at least are holding on to their gold reserves.I am holding on to my IGR as well as I can see a gold run up if the 1.5 trillion QE 3 gets the nod.

Angers

Central banks keeping gold in their vaults

by: Robin Bromby

From:The Australian

October 22, 201112:00AM

Source: The Australian

CENTRAL banks across the world, Australia included, seem to have decided to sit on their gold.

The era of governments losing faith in gold -- which led Australia to sell off 167 tonnes in 1997 at an average of $US350 an ounce (against its present value of more than $US1600/oz) -- is over.

In 1999, 14 of Europe's central banks forged an agreement to ensure orderly disposal of their gold stocks, and hundreds of tonnes subsequently went into the market. This was after the Dutch had sold 360 tonnes in early 1997 and the Belgians 203 tonnes.

Yet the latest figures for this year show no significant selling of the metal by the banks in recent months, even though gold still comprises a large proportion of some official reserves (74 per cent in Italy's case).

Australia's decision to sell off two-thirds of its reserves 14 years ago could have been disastrous for its currency but we were probably saved by a combination of the subsequent resources boom and the decline of the US dollar.

The rebound of the Australian dollar also has saved the Reserve Bank of Australia's reputation bacon: with our dollar at its present level, the RBA has forgone only about $6.5 billion in lost profit. Today, a low Australian dollar and a high gold price would have made the sale in 1997 seem a lot less clever.

The latest World Gold Council figures show the central bankers are sitting tight.

In August, The Philippines and Sri Lanka sold off small amounts of gold, Thailand bought 9.3 tonnes and Bolivia seven tonnes. But that's about it.

Since 1997, while other countries have disposed of the metal or bolstered their gold holdings (China increased its fivefold, while India bought 200 tonnes in 2009), the Reserve Bank of Australia has sat on its remaining 80 tonnes, neither adding to nor subtracting from it.

On the other hand, China -- now the world's largest producer -- is reported to be further boosting its reserves by buying newly mined metal.

This week, Kazakhstan central bank governor Grigory Marchenko said the bank would buy all the gold produced in that country for the next two or three years, or about 25 tonnes a year. The bank's gold holdings have increased by 30 per cent so far

this year.

The Reserve Bank sale caused a huge commotion at the time as critics queried the deal itself and also the fact it was not a good look for a country that was one of the world's leading gold producers.

Yet little has been heard about it since, and the Reserve Bank seems the Teflon central bank on the issue -- unlike the former British chancellor of the exchequer, Gordon Brown, who decided to dispose of much of the Bank of England's gold at between $US256/oz and $US296/oz in the late 90s.

His decision is constantly being dredged up, with several press mentions in just the past few weeks. Earlier this year, when gold went through a key level, London's Daily Mail headlined the news thus: "Gold hits all-time high of $1500 an ounce (which means the amount Gordon flogged for pound stg. 2bn would today fetch pound stg. 13bn)".

However, it's all very well to be wise after the event: in 1997 and 1998, faith in gold was at a very low ebb, and the gold bugs a very small (although obsessive) group.

One member of the Reserve Bank board at the time makes the point that, back then, Australia's reserves were too heavily skewed towards gold. Adrian Pagan, now an economics professor at the University of Sydney, said there had been similar controversy years earlier when Australia switched some of its reserves from sterling to the US dollar.

"There's no point looking back, Pagan says. "At the time it seemed a good decision." He says the bank was earning no interest from the gold and it was not as flexible as other instruments.

"It's a mug's game trying to predict what will happen 15 years later," he adds. "If I could look back, I would be in gold, too."

The board that made the decision sat under then governor Ian Macfarlane and included businesswoman Janet Holmes a Court, Pagan (then at the Australian National University), Westfield Holdings' Frank Lowy and the former Western Mining's Hugh Morgan.

Two weeks after the gold sale had been announced, the critics included former prime minister Malcolm Fraser, who wrote in The Australian that the sell-off had "severely tested" the Reserve Bank's reputation.

The announcement, he continued, "was naive, unnecessary and highly damaging to the world's gold markets".

Gold was then earning Australia $5.5bn a year, more than any export other than coal.

Two weeks after the Reserve Bank bombshell, gold sank to a 12-year low of $US314.50/oz.

There are still plenty of critics.

Sandra Close, author of The Great Gold Renaissance and whose Surbiton Associates charts the gold sector on a quarterly basis, notes that the Reserve Bank invested the gold proceeds in US dollars, Japanese yen and the German mark. "In retrospect, given the state of the US dollar and the euro, that decision does not look terribly smart."

The sale coincided with record goldmine production in Australia and signalled a lack of confidence in one of the country's top export earning sectors.

Veteran gold analyst Keith Goode of Eagle Research believes Australia dodged a bullet thanks to the resources boom and the greenback woes in the following decade.

"Any country that has sold its gold has ended up with a weaker currency," he says.

Which is, indeed, exactly what happened.

About the time of the gold sale, our currency was at roughly US75c. By April 2001, we hit a low of US48.39. Canada's dollar also declined after that country sold off 244 tonnes.

But then came along the resources boom and the ailing greenback.

"Now we have a strong currency. We did all right by default," Goode says.

He believes countries should hold about 5 per cent of their reserves in gold. The 80 tonnes sitting at Martin Place in Sydney constitute 9 per cent of our official reserves, which puts us in the league of The Philippines, Syria, Turkey, Russia and India.

Then there's another puzzle: gold holdings tell you little about a country's economy -- or do they?

Among the basket cases, the US has 74 per cent of its reserves in gold, Portugal 89 per cent, Greece 82 per cent, Spain 42.1 per cent and Belarus 41 per cent.

By contrast, look at Asia after a decade or more of blistering economic growth. China's official holdings of gold represent just 1.6 per cent of reserves. In Japan it's 3.7 per cent, South Korea 0.6 per cent, Malaysia 1.4 per cent, Singapore 2.5 per cent and Thailand 4.2 per cent.

But don't beat up on Brown too much: just on 18 per cent of Britain's reserves still exist in the form of the yellow bars stored in vaults.

http://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/mining-energy/central-banks-keeping-gold-in-their-vaults/story-e6frg9df-1226173510680

- Forums

- ASX - By Stock

- central banks keeping gold in their vaults

If the recent sell down in POG is causing IGR holders to sell...

-

- There are more pages in this discussion • 11 more messages in this thread...

You’re viewing a single post only. To view the entire thread just sign in or Join Now (FREE)

Featured News

Add IGR (ASX) to my watchlist

Currently unlisted public company.

The Watchlist

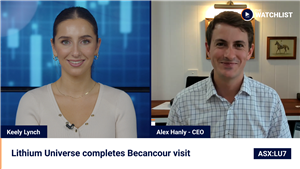

LU7

LITHIUM UNIVERSE LIMITED

Alex Hanly, CEO

Alex Hanly

CEO

SPONSORED BY The Market Online