ELON MUSK POWERS UP: INSIDE TESLA'S $5 BILLION GIGAFACTORY

ELON MUSK IS VENTURING HEADFIRST INTO THE BATTERY BUSINESS. HERE'S WHY IT MIGHT BE HIS BOLDEST BET YET.

BY MAX CHAFKIN

Elon Musk walks briskly onto the stage as hard rock blasts in the background. The guitar riff, which sounds like entrance music suitable for a professional wrestler or a minor-league cleanup hitter, fades out, and Musk surveys the crowd, nodding his head a few times and then sticking his hands in his pockets. "What I’m going to talk about tonight," he says, "is a fundamental transformation of how the world works."

The 44-year-old CEO of Tesla Motors and SpaceX (and the chairman of the solar energy provider SolarCity) is wearing a dark shirt, a satin-trimmed sports coat, and, at this moment, a knowing smirk. An admirer of Steve Jobs, Musk is an heir to the Silicon Valley titan in some psychic sense, but in a setting like this, he’d never be mistaken for the Apple founder. Jobs worked the stage methodically, with somber reverence and weighty pauses, holding tightly choreographed events on weekday mornings for maximum media impact. Musk’s events, which are generally held at the press-unfriendly hour of 8 p.m. Pacific time, have a more ad hoc feel. His manner is geeky and puckish. He pantomimes and rephrases, rolls his eyes, and cracks one joke after another—his capacity for expression barely keeping pace with the thoughts in his head.

Musk begins by showing an image of thick yellow smoke pouring out of a series of giant industrial chimneys, contrasted with the Keeling Curve, the famous climate-change chart that shows more than 50 years of carbon dioxide levels soaring toward a near-certain calamity. It could be mistaken for something out of Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth. "I just want to be clear," Musk says, with a nervous giggle, his accent betraying his boyhood in South Africa. "This is real."

His comments on this April evening, in front of a raucous crowd of Tesla owners (and some reporters) at the company’s design studio in Hawthorne, California, are quintessential Musk—weighty but also a bit cheeky. They’re also just preamble. His electric-car manufacturer is launching a new product line: large batteries that store energy in homes and even larger batteries that do the same for utilities and businesses. The Powerwall, a slender appliance designed to be mounted in your garage, comes in five colors and starts at $3,000; the Powerpack, an 8-foot-tall steel box that looks a bit like a utility transformer, is aimed at the energy industry and costs roughly $25,000. These prices are roughly half of what competing battery manufacturers charge.

Musk estimates that 160 million Powerwall batteries, combined with solar panels, would wean the U.S. off conventional power plants entirely.Photo: McNair Evans

"The issue with existing batteries is that they suck," Musk says. "They’re expensive. They’re unreliable. They’re stinky. Ugly. Bad in every way." The idea is to pair the new Tesla products with solar panels—either on the rooftops of homes or in large-scale solar farms—that will store energy during the day, when the sun is shining, so that it can be used in our homes, for free, at night instead of energy from power plants that produce greenhouse gases.

Musk thinks it just might be the key to solving the problem of global warming. He explains that if the city of Boulder, Colorado, population 103,000, bought a mere 10,000 Powerpacks and paired them with solar panels, it could eliminate its dependence on conventional power plants entirely. The U.S. could do the same with only 160 million of them. Then he offers even higher figures: 900 million Powerpacks, with solar panels, would allow us to decommission all the world’s carbon-emitting power plants; 2 billion would wean the world off gasoline, heating oil, and cooking gas as well. "That may seem like an insane number," says Musk, but he points out that there are 2 billion cars on the road today, and every 20 years that fleet gets replaced. "The point I want to make is that this is actually within the power of humanity to do. It’s not impossible."

astronauts) to the International Space Station. Tesla may be on a mission to rid the world of fossil fuels, but today, it’s a luxury-car manufacturer with a wildly successful product. According to Musk, the company’s Model S sedan outsold the Mercedes-Benz S-Class in the U.S. during the first half of 2015 and is on track to sell 50,000 cars for the year.

Tesla’s rise, in particular, has been stunning. Musk was widely mocked in the mid-2000s when he began describing a plan to build a high-end electric sports car that would be cheaper, better, and faster than a gas-powered one. Electric cars were known for being slow, impractical, and dorky, and no American entrepreneur had successfully established a car company of any kind since Walter Chrysler did it in 1925. Musk spent years deflecting criticism from pretty much every serious automotive expert and nearly went broke in the process. And yet Tesla’s designs not only made it onto production lines—they turned out to be amazing.

Better than amazing, even. The latest edition of the Model S, created by a team far removed from Detroit and led by a guy whose previous claim to fame was being fired from PayPal in a boardroom coup, received a score of 103 from Consumer Reports, which was a problem only in that Consumer Reports ratings are typically scored out of 100. (The magazine had to revise its scale in response to the record-breaking result. It has since tempered its enthusiasm after raising questions about the cars’ reliability, sending Tesla’s stock price plummeting.) The Model S also holds the highest safety rating ever from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

Now, Musk is doubling down, expanding the capacity of the company’s main car-assembly plant in Fremont, California (which will eventually produce hundreds of thousands of cars a year), while building a factory-to-end-all-factories outside Reno, Nevada, that will produce battery packs for both cars and homes. Over the six days following Musk’s presentation, which was posted on YouTube and the company’s website, Tesla reportedly received reservations for $800 million worth of Powerwalls and Powerpacks, about what it makes in almost three months selling cars.

"I think we’ve really struck a note, without salespeople or advertising," Musk tells me. "With that you can do anything."

"Do you know the difference between power and energy?"

"Uh," I start to respond.

"Do you know the units?"

I’ve asked Musk a question about improvements in battery technology, but instead of an answer, he’s decided to give me a pop quiz.

When I offer the right answer for energy—"Joules?"—Musk smiles. "Hey!" he says. "Not bad. What’s power measured in?"

Inside Mark Zuckerberg's Bold Plan For The Future Of Facebook

Seven Years Of Self-Improvement For Mark Zuckerberg And Facebook

Malala Strikes Back: Behind The Scenes Of Her Fearless, Fast-Growing Organization

Elon Musk Powers Up: Inside Tesla's $5 Billion Gigafactory

20 Moments From The Past 20 Years That Moved The Whole World Forward

The Future Is Now: A Photo Portfolio

In addition to serving as CEO, Musk was Tesla’s product architect, moving the company’s design studio to Los Angeles and obsessing over small details like the Model S’s light switches and door handles, while two teams of engineers worked in shifts around the clock. Tesla went public in 2010, and the Model S was greeted with rapturous reviews when it debuted in 2012, but the company nearly went bankrupt for a second time the following year when customers were slow to embrace an unproven car company offering unproven technology.

That the orders for the Model S eventually came in helped transform Musk from a sort of Silicon Valley eccentric—someone who was able to captivate the press but wasn’t always taken all that seriously by investors or his fellow CEOs—into someone who was seen, in the words of Ashlee Vance, author of Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future, as "America’s most adventurous industrialist." Vance’s book, which came out earlier this year, paints Musk as the lone entrepreneur willing to apply Silicon Valley thinking "to improving big fantastic machines" and who had created "the automotive equivalent of the iPhone."

Musk seems uncomfortable with this portrayal. When I suggest that getting into the home-battery business seems like an odd departure given that Tesla is a car company, he seems exasperated. "The goal has not been: Let’s make cars," Musk says. "The goal has been: We need to accelerate the advent of sustainable energy."

On top of everything else, Musk serves as chairman of SolarCity, the solar panel installer. (Musk’s cousins, Lyndon and Peter Rive, started the company after Musk pitched them on the concept while the three were driving to the Burning Man festival in 2004.) SolarCity and Tesla have collaborated for years in small ways, such as marketing solar panels to electric-car owners who want to charge their vehicles using sunlight. But Musk has long seen Tesla’s batteries as having applications beyond cars. Starting around 2007, he instructed his chief technology officer, JB Straubel, to begin researching the idea of using Tesla batteries attached to solar panels in people’s homes. "This has been something that has been in the back of our minds," says Straubel, who uses a hacked-together solar panel and battery system of his own in his Bay Area home.

"The biggest leverage we have in making electric vehicles more affordable for everyone is reducing battery cost," says Tesla CTO JB StraubelPhoto: McNair Evans

Musk sees his foray into home batteries as an inevitable extension of Tesla’s mission—and a necessary response to the basic facts of alternative energy in the United States. Solar power accounts for less than 1% of our total electric production in part because it has a significant limitation. As Musk puts it archly, "The sun doesn’t shine at night." Starting in the late afternoon, when a typical household is using a lot of electricity to run air conditioners, televisions, computers, and maybe the oven, the energy production of a solar panel plummets, falling to zero by sunset.

This gave Musk an idea: Why not just use the same batteries that power Tesla cars in people’s homes? People could charge the batteries when the sun shines brightest and then use them at night to drastically reduce their dependence on their energy company. "It’s pretty obvious really," Musk says. "In fact, that’s what my 9-year-old said: ‘It’s soooo obvious! Why is that even a thing?’ "

The drive from downtown Reno to the site of Tesla’s new battery factory takes 30 minutes or so along a mostly empty stretch of Interstate 80 that heads west through the high desert of the Sierra Nevada foothills. You pass the smokestacks of a power plant, the exit for the Mustang Ranch, Nevada’s first legal brothel, and wide expanses of brown scrub. On the day I made the trip, the landscape was covered in a thick haze from wildfires that were burning in California to the west, giving the place an eerie quality and making it hard to spot the herd of 1,400 roaming wild horses that still graze in the hills. "It’s very romantic," Musk had told me a few weeks earlier.

I don’t think he had only the horses in mind when he said this. Northern Nevada’s high desert is an ideal place for the technology industry, with its low wages, cheap energy, and a climate that may not be especially hospitable to foliage but is nearly perfect for data centers—and, as it turns out, for the manufacture of lithium-ion batteries. (Battery production requires very low humidity.) Moreover, there’s lots of room to expand, and Musk has already acquired around 3,000 acres of land, all of it previously unbuilt.

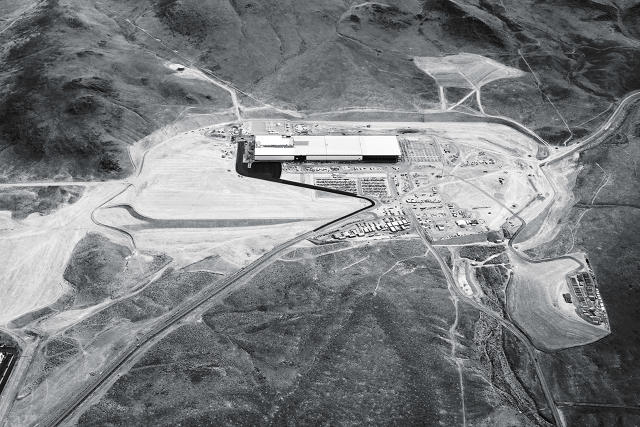

No journalist had ever before visited what Tesla calls the Gigafactory, which opens next year but won’t be completed until 2020. (And not for lack of trying. In October, a photographer from a Reno paper was arrested after sneaking onto the property and allegedly assaulting security guards as they tried to eject him.) Musk had warned me that the scale of the place would be overwhelming. "It will blow your mind. You see it in person and then realize, f*, this is big."

Tesla’s Gigafactory, being built outside Reno, Nevada, will be the second-largest building in the world by volume. "It will blow your mind," Musk says by way of warning.

He was right. It was impossible not to feel awestruck by the sprawling, 71-foot-tall structure stretched out, miragelike, before me as I drove into a shallow canyon. The building—which is so long that it has to be broken up into four distinct structures with four different foundations so that an earthquake can’t tear it apart—comprises 1.9 million square feet of factory space. That’s pretty big. It’s the size of a major shopping mall, but, as I was told by a senior Tesla executive, it accounts for only 14% of the total planned floor space, which will reach 13.6 million square feet. When the Gigafactory is finished, it will be only slightly smaller than Boeing’s Everett, Washington, plant, which is the world’s largest building by volume. The Gigafactory will be the second largest, and Musk has hinted it could grow bigger.

Despite all this, the Gigafactory is not some extravagance. Musk’s team is currently designing a much lower-cost Tesla car, the $35,000 Model 3, which promises the performance of a similarly priced gasoline car and a 200-mile range. But to offer that car in Toyota-like quantities, Tesla will need many more of the 18650 batteries used in its cars, as well as in its Powerwalls and Powerpacks.

A 18650 lithium-ion cell is 2.6 inches long and 0.7 inches wide, a stubby little cylinder encased in brushed metal. Hold one in your hand and you’d be forgiven for mistaking it for something that might go into your television’s remote control. In fact, 18650 batteries still power many laptops. However ubiquitous they may be, there aren’t nearly enough of them for Musk’s needs. "One hundred thousand is roughly the limit," Musk says, referring to the maximum number of cars Tesla could make each year if it bought all the world’s batteries, one-fifth of his goal. "So it’s either build a whole bunch of little factories or one big factory. And a whole bunch of little factories sounds like quite a bother. Why not just have one big one and maximize your economies of scale?"

I ask Musk why he didn’t simply make this a problem for Tesla’s main supplier, Panasonic. Battery manufacturing is not a high-margin business—Panasonic’s automotive division makes 3.1% margins—and it also happens to be one in which Tesla has no experience. He looks at me as if I were a California jury commissioner. "Why would they believe us?" he asks. "It’s hard to convince people from consumer industries that you’re going to make 15 times as many cars as you’re currently making. That sounds pretty implausible. We just had to say we’re going to do it, and you’re either on the ride or you’re not." (In 2014, Panasonic and Tesla signed an agreement that essentially makes Panasonic a tenant in the Gigafactory, manufacturing the cells and passing them to Tesla employees to put in battery packs.)

How Tesla's Commercial Batteries Have Changed The Future...For Winemakers?

Musk is more restless than Jobs ever was, but it’s hard to escape the sense that however proud he is of his accomplishments to date—the creation of several world-changing startups, the rehabilitation of the electric car, the rekindling of interest in space travel—it’s not enough. Jobs never talked about the distant future or what the iPhone might look like in 2050; for him, the iPhone of today was worth celebrating. Musk talks about the distant future incessantly and seems halfway ashamed by his past and current accomplishments. PayPal made him rich, but Musk has often suggested that the company could have been much, much bigger. Last year, at a conference, Musk suggested that key decisions regarding the Tesla Roadster had been "dumb" and that the company had erred by not designing the first version of its electric car from scratch. "It’s like if you have a particular house in mind and instead of buying that house, you buy some other house and chop down everything except one wall in the basement," he said.

In other words, Musk does not feel that the world would be okay if he died tomorrow in a horrific wing-walking accident. When I ask him what would happen if gasoline cars simply continued to improve in efficiency, he says, "I think people should be a lot more worried than they are," explaining that even if carbon dioxide levels remain what they are today, we won’t feel the ill effects until at least 2035. "Life will continue, but it will be a train wreck in slow motion," he says, perhaps resisting the temptation to note that no, we won’t all have to go live on Mars yet. "Millions of people will die; there will be trillions of dollars in damage—that sort of thing."

IN OTHER WORDS, MUSK DOES NOT FEEL THAT THE WORLD WOULD BE OKAY IF HE DIED TOMORROW IN A HORRIFIC WING-WALKING ACCIDENT.

Musk believes that the key to avoiding this fate will be inexpensive batteries like the Powerwall and Powerpack. In 20 years, he predicts, at least 10% of the world’s fossil-fuel power plants will be mothballed thanks to the batteries alone. After all, battery power would obliterate the need for so-called peaker power plants, which utilities run—almost exclusively on fossil fuels—mostly on summer afternoons to avoid brownouts when everyone turns on their air conditioners. "We have these big engines that we might run for three hours a year," says Mary Powell, CEO of Green Mountain Power, a Vermont utility. "They’re expensive to build and expensive to maintain." And if Green Mountain can’t make enough energy to meet its customers’ needs, it is forced to buy electricity from other states on the spot market—meaning it pays as much as 10 times the normal rate.

To try to avoid this in the future, Powell plans to offer the Tesla Powerwall to her customers as an add-on. For $30 a month, Green Mountain customers will get a Tesla battery that would save them in the event of a power outage while allowing Green Mountain to tap into the batteries rather than using backup generators when demand spikes on hot days. Eventually, she thinks that the savings from this approach could allow her company to give the batteries to customers for free.

But things really get interesting once Musk’s batteries are paired with solar panels. "In five years, solar panels will have three times the capacity and half the cost—and the storage will be much more efficient," says Ernesto Ciorra, head of innovation and sustainability at Enel Group, the Italian energy giant. Ciorra predicts a wave of disruption akin to the advent of mobile phones, as consumers in rich countries increasingly use solar panels and batteries to reduce their utility bills and those in poor countries use them to stay off the grid entirely. "The energy companies that follow this track will get more money," Ciorra says. "The ones that do not evolve will close."

Musk, never one to shy away from the social implications of a marketing message, says that in rural parts of Africa and Asia, having a solar panel and batteries "is the difference between having electricity and not having it." Of course, he also believes his new battery packs will appeal to Americans. "I suspect after a natural disaster the appeal of the Powerwall will increase substantially," he says. "You’ll know who has the Powerwall ’cause he’ll be the one guy in the neighborhood with the lights on."

Tesla employees say that in addition to making batteries cheaply, Musk has given them another directive: Make the factory beautiful. Tesla’s cars distinguish themselves by their performance, but Musk has always been attentive to the curve of a windshield or an intuitive door handle. Additionally, the Gigafactory must be attractive because Musk sees it as a product—something that has been carefully planned, where everything fits together with a certain harmony. He wants it to be beautiful, in part, because he plans to build more than one.

"We’re going to need probably, like, 10 or 20 of these things," he says. He pauses, raises his broad shoulders toward his ears, and smiles. "Somebody’s got to."

http://www.fastcompany.com/3052889/elon-musk-powers-up-inside-teslas-5-billion-gigafactory

RELATED: TIM COOK, ELON MUSK, TRAVIS KALANICK, AND STEPHEN COLBERT'S LATE-NIGHT DISRUPTION

- Forums

- ASX - By Stock

- TON

- Elon Musk Powers Up: Inside Tesla's $5 Billion

TON

triton minerals ltd

Add to My Watchlist

0.00%

!

0.5¢

!

0.5¢

Elon Musk Powers Up: Inside Tesla's $5 Billion

Featured News

Add to My Watchlist

What is My Watchlist?

A personalised tool to help users track selected stocks. Delivering real-time notifications on price updates, announcements, and performance stats on each to help make informed investment decisions.

(20min delay) (20min delay)

|

|||||

|

Last

0.5¢ |

Change

0.000(0.00%) |

Mkt cap ! $7.841M | |||

| Open | High | Low | Value | Volume |

| 0.4¢ | 0.5¢ | 0.4¢ | $3.86K | 777.0K |

Buyers (Bids)

| No. | Vol. | Price($) |

|---|---|---|

| 12 | 11693561 | 0.4¢ |

Sellers (Offers)

| Price($) | Vol. | No. |

|---|---|---|

| 0.6¢ | 1786211 | 7 |

View Market Depth

| No. | Vol. | Price($) |

|---|---|---|

| 12 | 11693561 | 0.004 |

| 9 | 3434286 | 0.003 |

| 4 | 2050000 | 0.002 |

| 4 | 6100000 | 0.001 |

| 0 | 0 | 0.000 |

| Price($) | Vol. | No. |

|---|---|---|

| 0.006 | 1786211 | 7 |

| 0.007 | 891944 | 4 |

| 0.008 | 1325790 | 2 |

| 0.009 | 781579 | 2 |

| 0.010 | 1500000 | 1 |

| Last trade - 15.49pm 14/07/2025 (20 minute delay) ? |

Featured News

| TON (ASX) Chart |