Is Novo’s Pilbara Discovery a Paradigm Shift in Economic Geology?

a.paul.gaudet 2 hours ago

Geology 101,

Market Commentary Leave a comment 201 Views

What I’ve been up to

October 28, 2015

Frankly, I was beginning to think geologists are just slicing the baloney thinner and just when I think we know it all something new comes along….

When I started writing “Straight Talk” in 2001 it was because I was increasingly uncomfortable with the half truths and deliberate falsehoods coming out of the mouths of a small number of rogue mining promoters. We were still trying to recover from Bre-X , yet some morons were still back to their old tricks to flimflam the public. Okay, there was an element of blatant self-promotion in my writings too I admit, but a long time ago I relinquished the cudgel to the Angry Geologist and his/her ilk.

However, the buzz around the Pilbara gold rush is really bugging me and I think it is time I wade into the fray.

Geo-Porn

To be entirely transparent, I am a shareholder of Novo Resources, and Quinton Hennigh was recently kind enough to devote two days of his very busy schedule to showing me around the project. I must admit that when I saw the July youtube video of fossickers metal-detecting nuggets

within solid rock and then jackhammering them out I thought this is the greatest legerdemain since Blackstone the Magician

.

Had Quinton lost his mind? I knew him to be a top-notch geoscientist who had paid his dues in the industry working for junior and senior companies alike. He had inherited my PhD project, Springpole Lake, in NW Ontario, after I had moved on, and had added a couple of million ounces of gold to it. A few months later I saw the “live feed” that was on-stage at the Denver Gold Show. Truly this was the greatest piece of promotion and showmanship anytime, anywhere since Phineas T. Barnum walked the Earth. Magnificent. I’ve been calling it “geo-porn”

.

My own piece of Geo-Porn

But although the Denver performance (they call it the “Party Trick” Trench) would convince even the most hardened skeptic, the Pilbara play exists almost in a parallel universe, unsung, unpraised and unmentioned by the majority of mining analysts – even though until lately it had a whopping market cap of over $1 billion Canadian. Part of this is due to unwarranted and unsubstantiated statements that the play is, or could be larger than the Witwatersrand Goldfield of South Africa. It seems to me that this passes as a credible statement in Australian mining circles, unless perhaps followed with the declaration, “And the dingo ate my baby!” Outside of Australia though the analyst community instead hears, “We have X billion ounces of gold…..and the Space Aliens put it there.” Those who want to lend credibility to the play are doing themselves no favours by making Bre-Xian statements and goosing the stock price for short term gain. The Novo discovery is hosted by conglomerate, but that’s where the resemblance to the Wits ends.

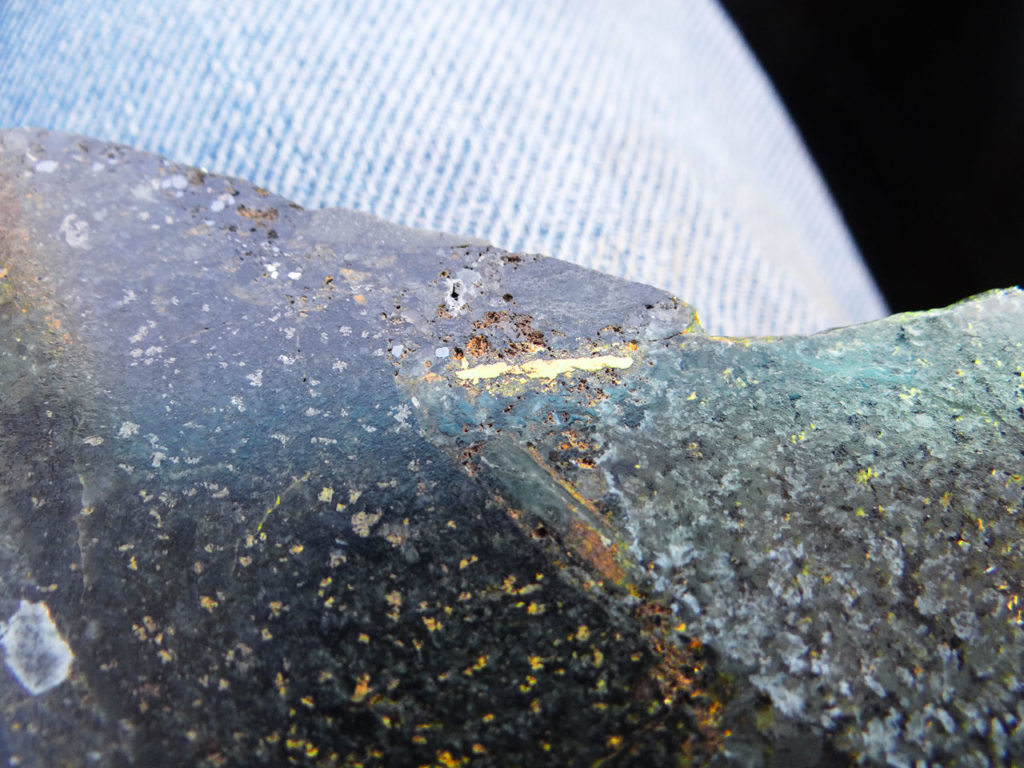

Slabbed piece of conglomerate from the Novo property, note gold nugget

Zoomed in on the nugget. Note the halo of fine gold particles.

Paleoplacer Pleasures

Back in 1998, I discovered some outcrops of quartz pebble conglomerate in the Gran Sabana National Park of Venezuela. I could pan gold out of the rotted rock. I heard rumours of an artisanal mining operation on top of one of the “tepuis”, or isolated flat-topped mesas in the park and rented a helicopter to investigate. Sure enough, there was conglomerate there too, and I found a nugget that was large enough to be caught in a 2 mm screen. I got the attention of Professor Lawrie Minter, a world-renown expert on the Wits, and of Hugo Dummett from BHP. Unfortunately, another Hugo, this one with the last name Chavez, came to power the end of 1998 and put the kibosh on any exploration plans. (Don’t worry, we didn’t intend to mine the park!) We moved the project over to the adjoining country of Guyana and over the next 2 years spent $15 million USD, largely from the Rembrandt tobacco group, to fund exploration looking for a Wits lookalike in the Roraima Formation. Lawrie gave me a crash course in paleoplacer deposits and set me up with a tour underground at Western Areas in South Africa. We spent a year working together, and got permission from Sam Hinds, the Prime Minister, to prospect in Kaiteur National Park on the Potaro River, and we staked a piece of ground the size of Belgium. Ultimately, and after much good geological work, we failed to find anything economic, but it was a helluva education.

Typical Wits lookalike of well packed, and clast supported rounded quartz pebble conglomerate

This exposure was full of heavy minerals and hence the rustiness. Gran Sabana Nat’l Park

I panned free gold out of this exposure. Notebook for scale. Gran Sabana Nat’l Park

The Witwatersrand contains tiny grains of gold, and certainly nothing that can be classed as a “nugget”. The gold lies in an “overmature” quartz pebble dominated, clast-supported conglomerate. The clasts are often imbricated, and there is abundant evidence of bedding, and crossbedding, and structures indicating river bars. The pebbles have a high degree of rounding and sphericity and are consistent with transport over long distances. Rounded, “buckshot” pyrite is a common feature. Rarely, diamonds and platinum are recovered in mining operations and these are consistent with paleoplacer, though because of the presence of minerals like chloritoid and gersdorfite, and absence of black sands, the Wits is considered by most geologists to be a “modified paleoplacer”.

The Novo stuff is immature and predominantly basaltic and other mafic clasts with occasional chert pebbles. There are some sandy lenses, but these are not quartz rich and reflect the same compositions as the conglomerate. The clasts are subrounded to subangular. Vein quartz is rare and there are no foliated basement clasts. I saw ripple marks in one outcrop only, but no crossbedding. The basal contact or “paleo-bedrock” is polished basalt or **bro with a vertical relief on the contact of up to 3 metres or so. The gold sits at or close to the basal contact, though it can also be found to lesser extent higher up in the stratigraphy. The gold is in macro-nuggets of 1 centimetre to 4 centimetres in size, in flattened discs with rounded off and folded-over edges. The nuggets resemble “corn flakes” when they are cleaned in muriatic acid….I guess the smaller ones look like watermelon seeds. In the rock you can see halos of tiny <1 mm gold grains displaced a few millimeters from the surface of the gold nuggets and perhaps these are some sort of remobilization during low grade metamorphism. There do not seem to be any rounded smaller gold grains, flake gold, flour gold or mustard gold which is strange. Typically, in a gold alluvial the most gold volumetrically is in the tiny stuff, not big nuggets.

I have my own theories as to how it got there, but I am staying mum on the subject for the time being.

Novo property right on the basal contact. Note the rounded clast.

There’s No place like Nome

Well, perhaps that’s not true. The paleo-environment appears to be consistent with Quinton’s idea that the thing is a marine placer, and similar to Nome, in Alaska

https://mrdata.usgs.gov/ardf/show-ardf.php?ardf_num=NM253, or the offshore marine alluvials off the west cost of South Island, New Zealand. If you want to know what that stuff looks like, just watch an episode of

Bering Sea Gold on the Discovery Channel

https://www.discovery.com/tv-shows/bering-sea-gold/ . Like most “reality TV” this is probably scripted and phony, however the vacuum dredging and gold on the bedrock surface is real.

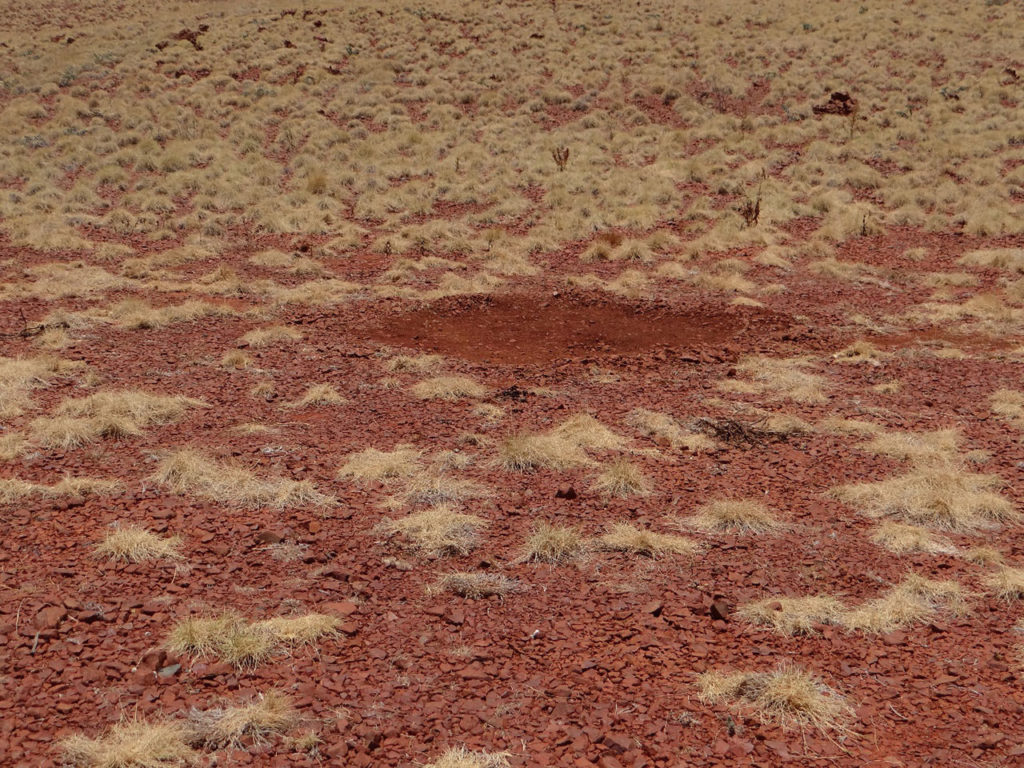

The Pilbara is a terrain worn down to its nubs. It is an empty country of chocolate brown hills divided up by dry washes and forlorn stands of eucalypts, with ochre red soils and spinifex everywhere. Without water and shelter from the hot sun you would last only a day or two out in the open. Quinton introduced me to an intrepid gentleman who the previous night had recovered 23 grams of gold from an area about 2.5 square metres, using a metal detector, a steel bar to break up the soil, and a shovel. Most fossicking is done at night when it is cooler. Since the Novo staff became Youtube stars a small army of metal detectorists has descended on the area. They are even using flashlights, hammer and chisel to excavate the pink bullseye targets sprayed on the rock for the Denver Gold Show video. Cheeky buggers. Quinton showed me almost a dozen places where the lazy had scraped the dirt aside with boots where the detector had indicated metal, or the more keen had excavated a couple of feet down. These are loose gold nuggets in the regolith soil on top of the conglomerate and represent a natural enrichment whereby wind and water winnow away the basaltic fragments and leave the heavy gold behind. There are some phenomenal surface grades and I expect that if this isn’t already a security concern it soon will be. In some cases the conglomerate is entirely worn away, and the rare but more resistant quartz pebbles left on surface indicate where it used to be, and a rich area to dig.

Decomposed conglomerate on surface, note quartz pebbles

Sampling Woes

In the last week or so we have seen much steam taken out of the play by numerous commentators’ hand-wringing that it will be difficult to near impossible to get a reserve number on this. What I am wondering is why anyone should give a damn? Sandra Close of Surbiton Associates is the latest one who has lost the plot

http://www.mining-journal.com/research/news/1309557/consultant-urges-conglomerate-caution .

Those of us with more than a few gray hairs in our beards remember those halcyon days when successful producing mines had no more than a few years’ reserves ahead of them at any time, and before the investment bankers pushed companies to determine reserves down to the last ounce before starting production. The Dome Mine in Timmins has finally closed after a more than 100 year run….for much of it there was only a defined reserve of a few years ahead of the miners, but it was obvious and intuitive that the mine had many years to run. In Canada, all of the greats, the Con, Giant, Campbell Red Lake, Kerr Addison, Wright Hargreaves, Lakeshore, Lamaque, and Hollinger-McIntyre were all run in the same way. Raising equity to drill it out to the Nth degree with expensive pre-production paper is a newfangled and insidious thing. In my personal experience, the Fruta del Norte deposit in Ecuador…which was pretty obviously going to be a high grade mine and which I participated in discovering, was shown by three major consulting firms to have an inadequate number of drills holes in it to determine a bankable reserve. It had been drilled on 100 metre spaced lines, at a nominal spacing of 50 metres for the entire strike length of 1300 metres. One consultancy said we would have to drill the thing on 23 metre centres to put together a reserve and give it statistical validity. This would have taken well over a few years and well in excess of $100 million in expenditure…and for what? Bragging rights? Kinross blew through $300 million drilling it out for reasons known only to them. Our little company, Aurelian Resources, was staring down the barrel of a gun. We would have had to push so much paper out to the market to raise that kind of money…well, it was pretty obvious that the only thing to do was to sell it. Back in 2013, Strathcona Mineral Services declared the resource at Pretium’s Brucejack deposit to be “invalid”….yet the mine reached commercial production July 3

rd of this year. The ultimate reason for this fracas is the “nugget effect”, which makes it hard to quantify the gold in the ground.

But back to the Pilbara play. Already and at this early stage it is pretty obvious that this is a large-ish deposit (no I am not gonna put a number to it) but it seems to me that almost everyone, except perhaps for Eric Sprott, who has a reputation for seeing value early, has

missed the point. What is the point you ask?

This thing is ostensibly at surface, so it is like mining placer gold! Now, I own and operate a placer sapphire and gold mine in the Treasure State of Montana, so I understand the difficulties of sampling where the nugget effect is an issue. The distribution of gemstones in alluvial gravel is almost random. Fruta del Norte, where the gold deposit lies circa 200 metres below solid rock is altogether a different beast from a fossil paleoplacer that lies at surface or maybe a maximum of 40 metres depth. There are tens of thousands of alluvial mines in operation around the world today. Such deposits are very forgiving because the costs of extraction are so damned low! It’s well known that in the California Tertiary placers worked by the ‘49ers only a mere handful of men struck it rich. This is because the rich gold lies in pay streaks or leads, usually on the bedrock. Years later when the dredges chomped through the alluvials, guts, feathers and all, there were monstrous fortunes made because they could employ economies of scale and cheap bulk mining to take the low grade as well as the remnants of high grade left.

It is unfortunate that the reverse circulation programme Quinton tried at Purdy’s Reward was a bust. As I understand it there was no return from the sampler cyclone unless you flooded the machine with water, thereby smearing the grade up and down the drillhole and making the samples essentially worthless. In Quinton’s shoes I would have trashed the samples too. They would cause more uncertainty than provide answers. There were certainly no guarantees that it was going to work; but the now planned bulk sampling programme is a far superior idea. Bulk sample pits all over the property are the way to go and they have to be large. If you look at the two original bulk samples the “sorted concentrate” (i.e. coarse gold) was 2.15% of the first sample and 1.82% of the second. This translates to 5.87 g and 4.90 g respectively, which maybe represents 2 or 3 nuggets each. You see how the nugget effect works? Out of roughly 270 kg of rock you get only 2 or 3 nuggets. If you maximize your sample to 20,000 kg (for which they are permitted) you should expect maybe 200-250 nuggets, which is roughly the contents of the Tupperware container full of gold from Quinton’s collection.

Quinton’s Tupperware container full of nuggets

In Montana, I can clearly see a couple of years’ production ahead of me at any time by having a dedicated sampling crew of students take 20 tonnes of gravel from each sample spot and run it through a portable recovery plant, and I know intuitively I’ve got lots of years ahead of me because I haven’t begun to sample 2000 or so acres of prospective ground. I “could” use a Banka drill and grid drill my entire property for a resource number, but what would be the point? So I can leverage the property and borrow against it? Aha! Do I smell an investment banker in the room??

Quinton has a unique deposit which presents a unique opportunity. You just have to stop applying the usual logic to it and think outside the box. He has already told me that his preference would be to “bulk sample” the thing till Doomsday, and make heaps of money doing it, but the rulebook might shut him down at some point….and he probably won’t be able to mine this thing on the scale he would like to. He says that he can’t get an operating permit without a reserve number. Well, here’s an idea, the Steinert XSS T sorting machine he has already used successfully requires no water or chemicals to operate…..so suppose Quinton applies to extract under a quarry license rather than a mining license? Is there anything stopping him? What’s it gonna cost for Quinton to get into production? He needs a couple of Steinert machines, a front-end loader or two, an excavator, a backhoe with a hydraulic rock breaker attachment, a portable screening plant, a jaw crusher and a roll crusher, and a few haul trucks. $10-$12 million US?? He’s got more than that now. In fact, Quinton may never have to go to market for money again! (ooooh the bankers won’t like that!)

Shallow boot scrape where a fossicker has recovered a nugget or two

Shallow pits in the regolith where fossickers have dug nuggets

It may never be possible to get a JORC compliant reserve number on this beastie

but it doesn’t matter. Quinton will demonstrate, by going back to first principles through his bulk sampling programme (i.e.

by doing it) that this will be the lowest cost gold mining in the entire industry….not through a geo-fantasy PEA abstraction. He will also demonstrate that he has years and years of gold-bearing conglomerate to chomp through. Unless he starts to get a bunch of duds in the bulk sampling the success already of the fossickers over some 8 km strike length tells me that this will be huge. How far and how rich down-dip? God knows…but it will be years before anyone needs to test that (unless of course you are pushed by one of those pesky investment bankers). Let me make a prediction. The Novo Discovery will be the lowest cost gold mine in the industry, by a massive margin. Maybe sub $100/oz! That’s what should be attracting people’s attention.

I can tell you that if this play were anywhere in Africa, Asia or South America, there would be 100,000 plus artisanals on top of it using sledge hammers, pneumatic drills, or pluggers and dynamite to get at the nuggets…and bugger the grade numbers.

It is there, it’s going to be mined by someone, and the ultimate grade and origins for the time being are just White Noise.

(20min delay)

(20min delay)