Alan Kohler here and I’m talking to Grant Wilson, who is the executive chair of Tivan Limited. This company used to be called TNG and I interviewed the CEO of TNG back in October, 2021. Not long after that, Grant Wilson launched a campaign to roll the board, an activist shareholder campaign, because he thought that they were building the company on lies, including, he says, things that Paul Burton told me in that interview. Anyway, Grant Wilson rolled the board and got himself appointed executive chair. Paul Burton left, the whole board left, he came in and sacked almost everybody and completely changed the company, changed its name to Tivan Limited and bought a new project called Speewah in the Northern Territory and off they go.

It's a vanadium project, they have vanadium processing technology which they’re now developing in collaboration with the CSIRO. So, look, it’s certainly an interesting story about how Grant Wilson rolled the board and then took over and he says, found that the place was a train wreck, and now he’s been fixing it up. So, apart from anything else, it’s an interesting story, an interesting investment? Well, that’s up to you, so have a listen and then do some more work. His name is Grant Wilson, the executive chair of Tivan Limited.

Table of contents:

Shareholder activism

Rolling the board

Projects on the go

CSIRO deal

Technology development

TIVAN technology

Revenue

Cash positionGrant, Chanticleer in the Financial Review said that you engaged in a masterclass in shareholder activism, take us through what you did.

Yeah, hi, Alan. They’re probably being a little bit kind, I wrote for the Fin Review for a couple of years and they covered the campaign through mid-part of last year and fair to say though, that it was a very unusual form of shareholder activism that I ran and ultimately prevailed with. This was a company called TNG, for your listeners, which is now Tivan. And to be fair to the Fin as well, they’re absolute professionals over there, so I went from being a columnist to the subject of these columns, which was a transition and they were obviously very professional throughout that.

Firstly, why did you start to run a campaign against the board of TNG and how did you do it, what did you do?

Late 2021, I noticed just a small holding in a company called TNG in a portfolio that I was liquidating, it was actually a bunch of lithium stocks and it had snuck in there and I looked at it closely and I said, “What’s that doing there?” I realised that the major project was near Alice Springs and I grew up in Alice Springs, which is unusual. So I had a close look at it and it didn’t look right to me from the start and I spoke to some locals and other people around the traps and I realised that it was probably…

What didn’t look right, what do you mean?

The representations, particularly on the costs. I obviously have a decent sense of what it takes to get things done out there. They’d also been kicked out of Middle Arm by the NT Government and locals such as Paspaley in Larrakeyah, so that was a read flag for me, and sort of scurried back to the middle of Australia claiming that they could build this project when there’s no infrastructure there. Once I’d spoken to some locals in Alice, I was sure the management was on the nose. They’d been working on this ostensibly for 10 to 12 years and so I started to buy into the register, I had a quick chat with the MD and started to accumulate a position, got up to about 2 per cent. You need 5 per cent as a minority shareholder to launch what’s known as a 249D action, this is true shareholder activism. The stock was not very liquid and so I got to about 2 per cent by Feb/March, the war in Ukraine and Russia had started and I got dragged back into some advisory work…

This is Feb/March, 2022, right?

Yeah, that’s right. I’d previously done some work for different governments in Russia and Ukraine, so I sort of got dragged into that for a couple of months around the gas stuff in particular, but came back to this in May/June of 2022, had another quick chat to the management team, set a few sort of trap questions, Alan, just confirming that they were lying to me and they were. And so, I had a chat to some other major shareholders in Australia who backed me and we got through the 5 per cent, I didn’t do much more buying, and we got to about 8 per cent which was sufficient to launch a hostile action against the board, requiring them to hold a general meeting where shareholders have that important statutory right to vote and that kicked off that process and they fought tooth and nail for several months.

In the middle of this, I interviewed the CEO of TNG, Paul Burton, in October, 2021 – so that was earlier than all this was going on.

Yes, you should disclaim that! [Laughs]

No, but how much of what he told me was correct, was true?

I’ve not watched that in full, but I can say or share that that interview, unfortunately, added to the lustre of credibility which he’d promoted for many years and I can assure you that he would’ve not been telling you the truth on that. It’s an unfortunate thing when a platform gets used like that, but he was quite adept at this. And there’s sort of an ecosystem around the company to be fair as well and I don’t want to say too much because there could still be legal proceedings on the other side of this. But, yes, unwittingly, Alan, you were a big player in this saga and hopefully it’s a cautionary tale for everyone involved.

I went through two phases – and this is really what it takes, the shareholder activism rules in Australia are stacked in favour of the incumbents, for example, they have the share registry, they can do call-outs, as they did, they put a private investigator all through my life, they put all this sort of spurious information over online platforms, they can use company money, whereas I had to pay my own way. We started off recognising all those traits and I built a website, actually, and started to do some ‘ask me anything’ sessions online with the retail shareholders, which is about 75 per cent of the company, then took it around the country where we did these awesome events in Brisbane, Melbourne, Sydney, Perth, just showing up and asking shareholders to come and we put on a bit of a show there, but it got people’s attention.

We knew we had the retail vote covered pretty much straight away, there was so much animosity towards management. But you have to get that turnout up because you have to win 50 per cent of the votes that are cast and typically, votes at a general meeting might be 20-30-40 per cent, so you’ve really got to work at it and you’ll find the institutional shareholders are very reluctant to participate in activism because it could send a signal that their business model is tilted in that direction and they will hold their cards right until the end – and that’s what happened in the first round, got all the way to the end and they knew they were gone, so they stacked the board. They brought in Neil Biddle, who had some market credibility from his time at Pilbara and that swung one of the insto shareholders late in the piece and that vote got split, Alan, it was like 50-50, so the Chair went, one of the NEDs went, Burton said he’d step down, so it did maximum damage on the first one, but it was basically 50-50, I missed. The craziest thing and why retail still believes this vote was rig, is that the voter turnout was up at 65 per cent for that, unprecedented, absolutely unprecedented. So it basically went quiet for a month and I think Neil realised that he’d bitten off way more than he could chew and I then relaunched – this is Neil Biddle at this point and he was sort of looking after Burton and basically stitching up an exit deal which was very favourable to Burton. The stock had fallen like 40 per cent on the outcome, from memory.

And so, because Neil had been appointed by the board as Chair, he still had to get confirmation from the shareholders at the AGM, so when the AGM nomination window rolled around, they tried to shorten it one day and close the office so I couldn’t nominate and the ASX jumped on them and in short, the five-day window for director noms was opened, I nominated, relaunched the campaign online and basically said, “Neil, it’s you or me to lead this company…” and he pulled out within about a week and then I had a glide path to takeover the company, effectively, and was confirmed as executive chair with a 96 per cent vote, late November, last year.

When you got into the company and actually started looking at it, what did you find?

Yeah, I’m on record as saying it was an absolute train wreck and it was.

What does that mean?

Precisely what it means, is that we put the company into project review. I campaigned on renewing and resetting and reviewing the project as well and that bought us three months of relief from continuous disclosure. I said this at the AGM last Friday, Alan, is that if we’d had to come forward in that month of December under continuous disclosure and explain how bad it was at the major project, Mount Peake, which had been held out to have a net present value of anywhere between, I think, $2.5 and $4 billion dollars for the better part of a decade, if we’d had to come out and true that up straight away the stock would have gone to zero and we would have liquidated the company, absolutely no doubt about that.

What instead we did, was we had three months to solve this very difficult problem, we had major problems with the resource and we had major problems in the technology, a flowsheet which they’d referred to as TIVAN, this is a technology that can break down these hard rocks into titanium, vanadium and iron, which was one of the main selling points of the company for a very long time. We scrambled and I basically terminated everyone that I could, service providers and staff that were non-key and I found one of our engineers…

Just to interrupt there, did you think of giving up and liquidating the company?

Alan, I did all this because coming from the Territory and I guess, being successful in my previous career and self-made, I knew that I was taking a huge risk and that there were various objectives that went beyond just shareholder returns and pecuniary rewards. I was looking to do something in the Territory and I was also mindful that there are these endemic governance problems in the junior resources sector. So I was always going to fight, it was just a question of whether there was paths, you know? Once you break it, you own it, I really did take that responsibility on and shareholders know that, I’ve stuck with it the whole way and I was fighting for them, they backed me, so I really felt that sense of responsibility to the retail shareholders – and they’d had a terrible time, you know, over a decade, a lot of them in at bad entry points, a lot of them had sold…

When you took over and you became executive chair, what did the company have?

Not much, mate, to be frank. We walked in and we did not have a viable project and we did not have a viable processing technology.

And the project was Mount Peake, right?

That’s right.

Are you saying it wasn’t viable?

Yes, I’m on record as saying that.

And how much money did it have?

In the bank, I think we had $7 million dollars. We had a market cap – I think the market cap had sunk to like $60 million and when I got in it was probably $80m to $90m, somewhere around there, so we still had the confidence and trust of the market, so it was a really unusual setup. You’re sitting there and you’ve inherited, in effect, these misrepresentations and you’ve got to find an alternative path. So, what I did do was, as I said, I sort of terminated everyone that was involved and that was an extensive process, but I was done within two weeks.

How many people did you sack?

Everyone inside the company, I mean there was only two people left, really, from the previous regime. But it was beyond that, it was the lawyers, it was the PR, there was a whole ecosystem of service providers around the company that knew and they were taking money out of the company, you know, to shelter…

That knew what?

That knew the project wasn’t viable.

So, what you’re saying, is the company was basically built on sand?

Yeah, Mount Peake is in the desert, so it’s an appropriate metaphor.

But the whole thing was based on a project that was not viable?

I think it’s worse in a sense that towards the end, management – and I won’t, again, say too much here – but they were taking out chunks of money for themselves and setting up offramps and this goes beyond things like termination payments. There was a tenement block in the middle of Australia which they’d purchased ostensibly to find lithium and they hadn’t disclosed that they’d put a caveat in this transaction and that caveat required up to $40 million dollars to be sent to the vendors in Vanuatu, Alan, where Mr Burton was on the board, if someone had found something significant. So they were effectively asset stripping towards the end, it was quite a serious situation.

Okay, but you’ve got some other projects now, so tell us about how you got those?

Yeah, what happened was one of the junior engineers – and he’s a brilliant, brilliant young man and he was in a moral quandary, I think, through much of this time. Nonetheless, he had the skillset, the integrity, the work ethic that I value and that I always look for in people that I work with and certainly when you’re trying to build a team and come back from a really difficult situation, it’s those sorts of people that you want to back. And so, I spoke with him extensively through those first two weeks trying to identify true north and just actually have the processing technology worked and where it might be redeployed. And so, I asked him to do an alternative resource study which was to say, okay, we’ve got this technology, we understand it’s got some problems but it is a breakthrough technology…

Did TNG own that technology?

Yes, it did and the engineer in question had worked on it and he had the best know-how, best handle on it. He’s a young guy, he’s still with us, he’s brilliant and without him, I’m not sure we could have transitioned through, to be frank, without his acumen, talent, dedication and moral clarity as well is very important in that sort of situation. So I put my trust in him, I asked him to do a study and within two weeks, he’d come back with the results, which was applying that technology to resources around the world. We found 15 comparable resources in places as far afield as Brazil and Canada and South Africa and then obviously in Australia. I asked him to do desktop studies in terms of project economics on each of these and he did that for me very quickly and it was a very comprehensive study.

There was one resource, Alan, that just stood out by so far and it was very clear to me that if we could get our hands on that resource, that we would have a viable company and in fact, an incredible pathway. That resource is called Speewah, it’s up near Wyndham, 100 kilometres south. I knew straight away that meant I had to take the company back to Darwin, into the Middle Arm Sustainable Development Precinct. So I had basically three months to pull off a high-wire act which was…

Who owned Speewah?

It was owned by a company called King River Resources and so the dual pivot, as I referred to it with the board – and the board backed me on this straight away, the new board – which was to take the processing site back to the Middle Arm Sustainable Development Precinct where TNG had been summarily kicked out of and I did that with the strong support of the NT Government, they were very agile, they listened…

Where is that?

That’s Middle Arm, that’s the famous Middle Arm precinct.

Where’s that?

It’s in Darwin, 20 k’s south of Darwin. This is the one where there’s a Senate inquiry now and it’s the one with the $1.5 billion federal equity investment. We view it as the most strategically important sustainable development precinct for common use in the country. So, with the support of the NT Government, I was able to get us back there as early as February and that was critical and we’re indebted to the NT Government for understanding the complexity and sensitivity of that situation. And with that, I was paralleling a negotiation with KRR, which was friendly, that was a friendly transaction – it restored my faith, to be frank, in the junior mining sector, to find a good operator on the other side of that transaction which we had to complete in such rapid time. So we completed that, end of February…

You bought Speewah off King River Resources?

That’s right, in stock and cash, in February. Then we had a primo location for the company in Darwin at Middle Arm and now, the best resource on the planet and it’s not close. They’d worked on it for about 10 years, they’d never really had intentions of developing it but we bought the data room and we bought all of the relevant licences. They’d never tried to convert to mining licences, they had some concerns that they’d walk into difficulties with traditional owners, but I had very, very strong relationships across the traditional owner domain and so that was an opportunity, in a sense, for us.

If it’s such a fantastic resource, how come King River didn’t want to develop it?

It’s sort of like the apocryphal $10 dollar bill, Alan, you’ll know from efficient capital markets hypothesis, you know, the economist that walks along a road and sees a $10 dollar bill and doesn’t think it’s real because someone else would have picked it up, it’s sort of like that. I think as well that vanadium wasn’t as sexy as it is right now, Australia’s tried to do vanadium off and on, there’s been failures at Windamara, **anintha’s now paralysed, that’s between AVL and TMT. But it’s fair to say the tailwinds in energy transition are right behind us now, obviously the climate change agenda, but this concept of critical minerals building sovereign capabilities, downstream value addition, the hard break from China that’s occurred over the past five years, has made it much more possible to raise the money that’s involved.

I think as well, we just have the energy, we have the team, we have the expertise and we can apply the technology. It’s been redeployed, it’s been re-shored. Most recently, we’ve done a deal with the CSIRO which is incredibly important – but King River had none of those things, so it was just a match made in heaven. He was looking to sell, we were looking to buy and we got the deal done.

How much did it cost you?

That was $20 million dollars and that was half scrip, half cash and we deferred some of the cash. And so, KRR’s now one of our major shareholders at Tivan, I think they own around 6 per cent of the company, very harmonious relationship, we locked their shares up for a couple of years and it’s been fantastic to have that win-win for both companies. They’ve been able to take some of that cash back into some gold exploration they’re constructive on around Tenant Creek. It was just a perfect transaction – I referred to it on Friday, Alan, at the AGM, as the transaction of a lifetime and I think that goes both ways, I know KRR’s very happy with what’s happened.

Tell us about the deal you’ve just done with CSIRO?

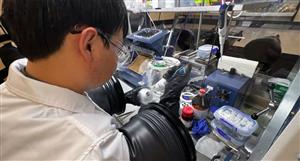

The technology was also in a difficult place, they’d worked on it for ages and there were issues with it. To me, the main issue was the development of technology had been imperilled because it was running through long programs of test work in European labs with one of the EPCs involved and a couple of other European companies. I saw that through the prism that I operate in, which is geopolitical and macro and so on and so forth and I knew that this agenda was coming from Canberra about sovereign capabilities, we’d been involved in that. So, to me, it was like, okay, we’ve got to get that technology back to Australia. Happily, I was talking with and engaged with CSIRO very soon, like two weeks after the change of control and they’d been working on something similar on a parallel track, independently of TNG, for about three years.

And so, we put the teams together in February, it was like an eight-hour workshop and we realised quickly that there was an integrated path and that there was this opportunity to collaborate on a pathway. We announced in April, a non-binding relationship and I’m really pleased to say that we matured that agreement into binding form about two weeks ago and the chief executive, Dough Hilton of CSIRO, signed off on it. I think it’s an exemplar of how CSIRO’s mineral resources team can work together with even a company in the junior resource sector because it involves revenue sharing down the track and they’re very much about impact, you can imagine, CSIRO, they want to have national impact and if we get this up and going through a pilot and then deploy it, this technology has the capability to disrupt multiple industries and to deliver vanadium at a cost point which will be radically different than even what China can manage and we’ll have that vanadium in Australia, Alan, we’ll be able to do batteries. The big green Australian battery dream is alive at Tivan. It will never happen in the lithium sector, in my view, you have to mass produce these cells, it’s always going to run through China because of the chemistries, but vanadium batteries is just vanadium and water, it’s an aqueous…

Is the TIVAN technology that you own, that the company owns, is that a vanadium processing technology?

Yeah, as I mentioned, it takes the hard rock…

Is it more than vanadium or just vanadium?

It’s titanium – so the name of the company, we renamed the company, rebranded it completely, we’ve transformed everything, governance, the board, the team, comms, an we now call the company Tivan, and that’s titanium and vanadium. The technology is specifically designed down a hydrometallurgical route, so we’re using hydrochloric acid to break down these hard rocks into those constituent commercial products and have three revenue streams. That’s why it is exciting, but there’s a pathway ahead which has to run through a pilot. You could tell from the outset, I think, with TNG, certainly if you had experience, the fact that they hadn’t built a pilot, the fact that the EPCs never issued process guarantees, you knew that there were problems in that technology, that’s what I could tell from the outside and that was confirmed.

What I didn’t anticipate was that we’d have this wonderful collaboration with CSIRO on the other side, where we’re working together in a national interest now for the next 20-25 years, it’s a really long-term agreement, so it’s a real landmark agreement with CSIRO, we’re super excited about it.

Right, but the point being, the technology needs further development, right? I mean, that’s why you need CSIRO to be involved?

Yeah, that’s fair and there were issues in the flowsheet, there were issues simply with the capex that was coming out of it and the CSIRO breakthroughs address a lot of that. I think, for listeners, Alan, it might be helpful to understand my vantage point on this, because I’ve come from high finance, I’ve come from government, I’ve traded commodities for a long time but I’ve never been involved in this level of detail and been exposed to it. What I saw on the way through, was just this incredible complexity, you start to appreciate how precise this technology needs to be, how often times the challenges are to do with the interaction between the minerology and the technology, how much test work needs to happen. I view it as almost like an arms race now, Alan, you could see this in lithium, rare earths, cobalt…

Okay, Australia’s got these fantastic resources, but if we’re going to move downstream, we have to also have this incredible technology and we’ve got the smarts, you know, there’s some great engineering schools and CSIRO’s just in a different league altogether, but if we’re serious about this sector, we need to have the IP, we need to have control over those development pathways. And yes, they’ll take time, but we’ve got a path in this instance and that’s fantastic, because if you end up on the other side of that in the case of Tivan, you’re talking about having the best resource on the planet and the best technology on the planet, right, then you are untouchable. Tivan now has the foundations to dominate the global vanadium industry, even over and above China.

Can you tell us how the deal with CSIRO works? You’ve got a technology licencing agreement, right? It’s 20 years long, did you say, or 25?

Yeah, there’s two aspects to it, which is a licencing agreement and that means that if and when we get the technology deployed at Speewah, that there’ll be a revenue component for CSIRO to enjoy and they can take that back and invest in further R&D for the country, so it’s perfectly aligned in that sense. At the same time, there’s a facilitation agreement which involves CSIRO and Tivan working together and that means we’ve got priority access to the labs, the team. The teams are so integrated, Alan, you know, there’s like six people at CSIRO, I’ve been working so closely with them all year, along with our team, and so it’s a really fascinating collaboration, great sense of comradery and real collegiate ethos. I see us working in lockstep and through the pilot phase in particular, so taking the technology out of a lab to a large scale pilot which we’re planning to build at Darwin and that’s where you can move from grams to kilos to tons and you can have financiers, independent technical experts, engineers come through, inspect the technology. That’s what you need, if you’re going to have a step change, you have to have one of those large scale pilots for sure.

Did you have to give up much of it…?

No.

What percentage are you giving to CSIRO?

That’s all commercially in confidence, but fair to say that if you’re paying away future revenue, there’s that alignment and from our point of view, the collaboration, the association with CSIRO, the cache, but also just that capability, Alan, is so important. We think it’s unique. CSIRO’s main focus is to have impacts and they’ve singled us out, in a sense, they’ve anointed us as the one and again, that’s a product of the resource that we have. But I think the team we’ve put together, for example, Professor Maria Skyllas-Kazacos, the inventor of vanadium redox flow batteries, has joined us, which is an incredible step, she’s never don’t hat before; we have the Head of Rio Tinto’s Iron and Titanium business globally; we have Dr Guy Debelle, you know, former Deputy Governor of The Reserve Bank; Christine Charles, a very well-known director, multiple boards, Government and research. We’ve put together an incredible A-list team this year and I think that gave CSIRO a lot of confidence as well.

What’s the resource at Speewah, how much vanadium and titanium is there?

The uplift is remarkable, in the sense that you’re going from a vanadium in concentrate grade at Mount Peake of 1 per cent, the resources in Western Australia around 1.4. Speewah’s up at like 2.4-2.5-2.6, so it’s the highest vanadium in concentrate grade resource of hard rocks in the world. There’s one in Brazil which is close, but it’s a very small resource. Speewah is monumental in size, Alan, it’s pushing 5 million tonnes, so we’re talking about a resource which is genuinely a strategic endowment for the country and we’re really intending to look after it, that’s why we’re working so closely with traditional owners. So, think about a project life pushing to 300-400 years, so this is really a game-changer, this is the Greenbushes or the Mt Weld of Vanadium. On top of that, it sits on the surface, so we don’t have to dig down, strip ratio is 0.4 and it’s just 100 k’s from port, which is fantastic in terms of opex. So, it’s all setup, Alan, it’s an incredible resource and we’re thrilled to have secured it.

To what extent do you need the TIVAN technology that you’ve got and you’re now developing with CSIRO, you need that, to develop the project? When will all this come together, the project’s ready to go and the technology is ready to go as well?

In Q2, we announced what we referred to as a fast track, so we’re all action here, Alan, we’re operating at velocity pace. The year that we’ve put together has not been seen before in the junior resources sector, I did 10 deals this year and we’re still not done, I’ve still got December to go, I’m heading back up to Japan. In Q2, I announced a fast track, this was taking known technology just to get the vanadium and get the company to revenue and to market as soon as possible, so we’re doing that at a minimum viable size. The FID for that is like 2026. The TIVAN tech is on a longer timeframe, so that journey through labs, pilot, happens in parallel and we think the tech will be sufficiently mature to build out around 2030 at this stage. But by that point, you’ve got a mine and you’ve got beneficiation and the first two steps on the fast track are identical to what we need for CSIRO and we’re projecting just this step change increase in demand function for vanadium as the grid storage market matures and we want to dominate that, we really do, we think we can. A fascinating aspect, Alan, is we expect to sell around half the vanadium into Australia to do large-scale batteries in places like Middle Arm, Port Hedland and 50 per cent likely goes offshore, but we’ll have this unique aspect where we’re going to be selling vanadium in Australia, in Australian dollars at fixed prices and that takes a lot of risk out of the project finance rounds.

Who to?

Well, we’ve got a technology partner on the batteries and we’ve got latent demand at places like Middle Arm. If you have a good look at Middle Arm, you’ll see not just incumbents that need large-scale grid storage, but a whole group of participants coming to town, building massive solar projects. So, we’ve partnered up with Sun Cable, for example, now owned by Quinbrook, and that’s the largest solar project in the world. Samsung’s trying to do the same thing, you’ve got Total Eren trying to do the same thing. What do they need? They need the corridors from the solar panels to Middle Arm, the transmission specifically and they need large-scale grid storage batteries and this is what vanadium batteries do, they can store energy for 4 to 24 hours, the vanadium electrolyte is practically indefinite, so as you get into levelized cost for these longer duration hours, it’s the best technology on the planet. The hold up’s been the lack of scalable and secure vanadium and that’s what we’re going to fix.

When do you think you’ll get the company to revenue?

We’ve got a few other revenue sources, we think, in the short-term, so we’ve got some assets which we’ll likely sell and we’ve got an exploration package down in a place called Sandover, where we have found lithium and copper, so there’s some exciting steps, I think, ahead next year where we can get creative – and you’ve probably gathered by now, I’m quite creative, I’m good at solving problems. In terms of the broader project, it’ll be a one to two-year build, so more like 2028.

Right, and when you say you’re going to sell some things, would you sell Mount Peake? Is it saleable?

Mount Peake is complex and again, just coming back to the start of the conversation, I guess, Alan, one of the things I’m really looking to do with Tivan now to stamp it as an authentically Territorian company and a champion and I’m focused on maximising our deliverables in the NT, moved headquarters to Darwin, just hosted our AGM there as well, it was a fantastic event, all these people from Darwin showing up just to learn about the company, even though they weren’t shareholders, the stakeholder outreach has been incredible. We did a big deal in Darwin recently with Larrakeyah traditional owners of Darwin and we’ve got significant advances already with Central Land Council, Kimberley Land Council…

So we’re localising a lot of what we’re doing and Mount Peake may still have a role, it’s an interesting resource, as currently defined though, it’s not where you’d want it to be, it’s just too far away from what it is. But there are other moves that we’ve got afoot and I think, watch this space, Alan, watch this space!

Did you say you reckon you can get the company to revenue in 2028, is that what you said?

For the main project, this is Speewah, and so you’ve got to work through PFS, which is Q3 of next year for us and then DFS, FID. As I said, we’re moving so fast, it’s a remarkable set of achievements.

These things take time, I get it, but I’m just wondering how you’re going to fund the company in the meantime, you just have to keep raising equity, will you?

Yeah, there’s two paths. There’s organic cap raises, we did one midyear, for example, which we priced at a 1 per cent discount and again, most companies are raising down 25 per cent, 30 per cent this year. That illustrated our differentiated approach to capital markets. Strategic investment, Alan, is interesting. As part of the AGM, we asked for placement authorities to be reset and were gratefully backed by major shareholders. So we swept all the resolutions as high as 99 per cent for most for them. So, with the placement authority, that means we can sell a strategic stake, Alan, and so we do actually have a number of companies and funds in long-term due diligence, so this is like long processes, they’re in a data room, if they were to partake in strategic investment then they have to lock that up for one to two years, sort of thing.

So there’s various ways that we can manage, but what we’re doing is creating alignment. I think a lot of the problems in the junior resource sector, Alan, is just the lack of alignment between management and shareholders and so, even with our incentives, we ripped apart all these old schemes, there was like loans for shares, participation rights, all this nonsense, and we just went with simple, clean, long-dated options and hopefully our shareholders will receive some of these options as well soon. And so, we have to get the share price up to 30 cents for management or the team to partake in those sorts of incentives over the project delivery horizon, which is 2026, so that becomes a fulcrum for the firm and for shareholders and always about alignment, Alan, just creating that strong sense of alignment between stakeholders, shareholders, management, the team, I’m always about alignment, durable alignment of interest, it’s just the way to go.

So, at September 30 you had $2 million cash in the bank, I presume you’re going to have to raise some more, are you raising more now?

Yeah, we had some R&D tax credits due this quarter as well, so we’ll make the right decisions at the appropriate time.

Right, good to talk to you, Grant. Thanks.

Thanks, Alan.

That was Grant Wilson, the executive chairman of Tivan Limited.

- Forums

- ASX - By Stock

- TVN

- Tivan - One Year Anniversary Interview

TVN

tivan limited

Add to My Watchlist

1.19%

!

8.5¢

!

8.5¢

Tivan - One Year Anniversary Interview, page-16

Featured News

Add to My Watchlist

What is My Watchlist?

A personalised tool to help users track selected stocks. Delivering real-time notifications on price updates, announcements, and performance stats on each to help make informed investment decisions.

(20min delay) (20min delay)

|

|||||

|

Last

8.5¢ |

Change

0.001(1.19%) |

Mkt cap ! $176.8M | |||

| Open | High | Low | Value | Volume |

| 8.8¢ | 8.8¢ | 8.4¢ | $40.03K | 473.4K |

Buyers (Bids)

| No. | Vol. | Price($) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 32790 | 8.4¢ |

Sellers (Offers)

| Price($) | Vol. | No. |

|---|---|---|

| 8.6¢ | 50000 | 1 |

View Market Depth

| No. | Vol. | Price($) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 32790 | 0.084 |

| 2 | 160325 | 0.083 |

| 2 | 16296 | 0.081 |

| 7 | 462448 | 0.080 |

| 1 | 20000 | 0.078 |

| Price($) | Vol. | No. |

|---|---|---|

| 0.086 | 50000 | 1 |

| 0.088 | 38682 | 1 |

| 0.089 | 116842 | 3 |

| 0.090 | 100000 | 1 |

| 0.091 | 50000 | 1 |

| Last trade - 15.53pm 11/07/2025 (20 minute delay) ? |

Featured News

| TVN (ASX) Chart |

The Watchlist

VMM

VIRIDIS MINING AND MINERALS LIMITED

Rafael Moreno, CEO

Rafael Moreno

CEO

SPONSORED BY The Market Online