Where should a smart investor park their savings in this current market, where stocks are expensive and continued low interest rates make income-yielding investments a joke?

In a word: commodities. Forget about trendy cryptocurrencies or tech. We like investing in tangible things that create real jobs, real money and real wealth, particularly now, with inflation becoming a threat to purchasing power.

Commodity prices rise and fall with economic conditions. Conventional wisdom has it that commodities tend to do well during late expansions and early recessions. As the economy slows, interest rates are cut to stimulate the economy, the US dollar falls and demand for commodities, which are priced in USD, goes up, along with commodity prices.

A commodities “super-cycle” can happen in the late stages of an economic expansion, when growth is so strong, companies can’t produce enough commodities to keep up with demand. The last super-cycle was 2004-08. From the bottom in 2003 to the peak in 2008, commodities rose over 300%.

The commodities super-cycle of the 2000s collapsed in the Great Recession of 2008, then resumed from 2009 to 2011. It ended in the bear market of 2011-15.

Many are pointing to the formation of a new super-cycle, driven not by fossil fuels and the rise of China, such as occurred in the 2000s, but by so-called “green” metals needed to electrify and decarbonize, to avoid the worst effects of climate change.

On top of surging demand for metals needed to feed so-called “green infrastructure” programs, we have current and emerging structural deficits for several metals, that will keep prices buoyant for the foreseeable future.

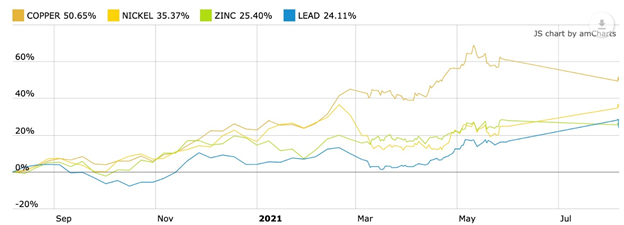

Over the past year, tight supply is reflected in the rising prices of copper, nickel, zinc, and lead.

Source: **promotion blocked**

Source: **promotion blocked**

As countries continue to innoculate en masse, and covid-19 infections, hospitalizations and death rates fall, re-invigorated economies are stoking demand for cars, electronics, clothing, and infrastructure for urban renewal, like new roads, bridges and water systems.

The US economy is running hot, owing to massive federal stimulus and a waning coronavirus pandemic (even factoring in the recent surge in cases due to the Delta variant), and that has caused demand for goods and services to outstrip the ability of companies to supply them.

Toss in virus-related supply chain bottlenecks, including a shortage of labor in some industries, rising freight rates, and companies having to frantically restock drawn-down inventories, amid high demand, and we have the biggest inflation increase in more than a decade. Consumer prices marched 5.4% higher in June, the biggest monthly gain since August 2008. Excluding food and energy, inflation increased 3.5% year over year in June, the highest reading since 1991.

Moreover, US inflation is actually higher than advertised. As Joe Carson writes in ‘The Carson Report’, Core producer prices for intermediate materials and supplies increased 2.3% in June. Since the start of 2021, these prices have increased at an annualized rate of 32%. That surge is the largest in nearly 50 years and is a harbinger of more consumer price inflation in the months ahead…

Carson also points out that the record rise in US housing prices is not part of inflation readings. If housing was included, it would push current CPI readings close to the double-digit gains last seen during the 1970s:

That means the US is experiencing a more significant “inflation bubble” than is being reported or recognized by everyone. Investors forewarned.

Beyond the US, Canada’s inflation rate hit 3.6% in May, the fastest pace in a decade. It dropped slightly in June but is still outpacing the Bank of Canada’s target. Prices are also climbing in the UK, with inflation forecast to reach 4% this year. With most businesses open and reporting strong sales, the British economy is expected to grow at a break-neck 8%.

Commodities are considered one of the best places to park investment capital during periods of rising inflation.

The reason is simple. As demand for goods and services rise, so do their prices, along with the raw materials (commodities) needed to produce the finished products. Investing in commodities is therefore considered a hedge against inflation.

Permanent vs transitory inflation

We’ve been writing a lot lately about inflation, and especially, the question on many investors’ minds: Are across-the-board price increases a temporary phenomenon that will eventually fade away and return to normal, or should we expect them to stay elevated, long term?

As forecasters and investors, we know the answer is critical. If an inflationary trend is forming, similar say to what happened in the 1970s, when inflation soared close to 15%, we had better divest our holdings of stocks and bonds, which tend to do better when inflation is steady or slowing (faster inflation lowers the value of future cash flows). Holding a bond makes little sense when inflation is rising because returns are diminished. A bond yielding 2% interest will at the end of one year be worth 3.4% less, if inflation is running at 5.4%.

We can look to history for guidance of which direction inflation might be heading. In a recent article, Streetwise Reports argues that Commodities were far-and-away the best performing asset class in both of [the 1940s and the 1970s], the two decades that come closest to our current economic situation.

That makes perfect sense given the rate at which prices were rising, far quicker than currently. In the 1940s, high government debt owing to wartime spending and large deficits relative to GDP, along with low interest rates, led to two sharp increases in inflation, the first in 1942 when the CPI peaked at 13.4%, and the second after the war in 1947, when the Consumer Price Index ran to 19.7%, the biggest increase of the last century.

Some inflationistas point to the 1970s as a better analog to present day, given that inflation climbed gradually, like currently, and lasted more than a decade. Inflation rose in three waves in the late 1960s through the 1970s, reaching a peak of 14.7% in 1980. Then Fed-Chair Paul Volcker made the drastic mistake of suddenly hiking interest rates, to curb inflation, which sparked a recession lasting into the early 1980s.

A historical comparison between the current and previous two periods is problematic, though, due to the fact that the US was on the gold standard during the 1940s, and the dollar was unpegged from gold by the Nixon administration in 1971.

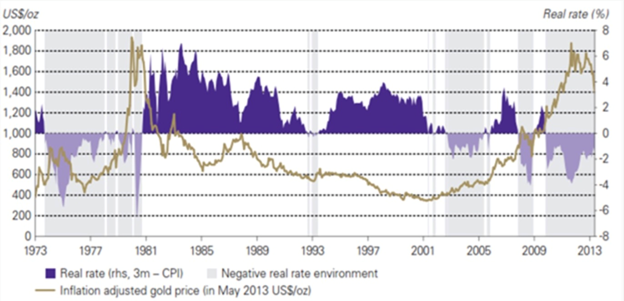

There are, however, two useful observations from the Streetwise article’s analysis. One is that both regimes, along with today’s, share negative real interest rates. This is easily calculated by subtracting current inflation of 5.4% from the benchmark 10-year US Treasury yield of 1.2%, leaving a negative real rate of -4.2%.

We know from previous articles that negative real rates correlate positively to gold prices. In other words, gold prices rise when yields after accounting for inflation go below zero.

In an article titled ‘The Golden Dilemma’, authors Claude Erb and Campbell found a near-perfect negative correlation of -0.82 (-1 being a perfect negative correlation) between real interest rates and gold prices between 1997 and 2012. Going back further in history, when real interest rates turned negative during the second half of the 1970s, gold moved as high as $1,900 an ounce, as real rates plummeted as low as -6%.

Historical rate of inflation vs gold

Historical rate of inflation vs gold

The second observation is concerning what happened after the gold standard was abandoned in the early 1970s. The Streetwise article states:

Unlike the 1940s, when the US dollar was still pegged to gold, in the 1970s we had the abandonment of the gold standard which marked the onset of five decades of limited financial and monetary discipline ever escalating to the historic macro imbalances we have today.

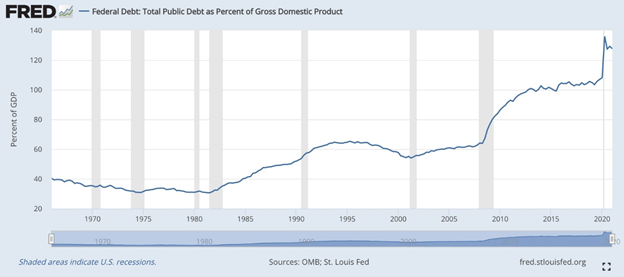

When the dollar was pegged to the price of gold, politicians were limited as to how much they could spend. Without a gold peg, they were free to spend indiscriminately. Fiscal discipline went out the window and the debt to GDP ratio soared. From just 30.9% in the first quarter of 1980, the ratio has more than quadrupled, it now sits at 127.6%, meaning that the debt is presently larger than the size of the US economy and increasing rapidly, especially as trillions more spending is planned for covid-19 relief and economic recovery.

Not only has the US national debt increased alarmingly, to its current $28.5 trillion, owing one could argue to continued money-printing without a gold backstop, the inflation rate has compounded.

Inflation doesn’t reset itself each year, it gets added to the previous year’s principle. If you have 3% inflation one year and 5% the next, the 5% in Year 2 is added to the 3% increase in Year 1. That is why the purchasing power of the US dollar has gone from $1 in 1912 to about 2 cents today — it has lost 98% of its value and that purchasing power is never coming back.

Even Fed Chair Jerome Powell admitted that prices won’t go back to where they were.

This gives additional credence to the argument that inflation, compounded every year, and without a gold standard to enforce fiscal discipline, is indeed permanent. It’s also fixed in policy. The US Federal Reserve aims to have inflation rise 2% every year. When the target is missed, a central bank becomes concerned the economy isn’t growing fast enough and will intervene to goose economic growth, typically by lowering interest rates.

And while policymakers continue to promote the view that inflation will drift back down to the 2% mark, without offering a plan as to how that will happen or when, our analysis has found there are nails in the coffin of the transitory inflation thesis.

For example one of the most important factors driving food inflation is climate change.

A recent article in the LA Times states that the world is facing unprecedented levels of drought, with nearly half of the US Mainland afflicted, and no continent except Antarctica spared. Besides the US and Brazil, other areas being subjected to drier than normal conditions right now include Madagascar, where hundreds of thousands of people have been left on the brink of starvation; and Mexico, which is releasing silver iodide into the clouds to stimulate rain.

World drought map. Source: National Centers for Environmental Information

World drought map. Source: National Centers for Environmental Information

The “heat dome” that covered much of western North America at the end of June shattered temperature records, isn’t the only weather event making headlines. There have also been unprecedented rains followed by catastrophic flooding in China and Europe, and temperatures reaching 49 Celsius in normally temperate Finland and Ireland.

In central Brazil, the worst water crisis in nearly 100 years has made navigation on one of the country’s most important river systems difficult, making it more challenging and costly to get its chief commodities exports to global markets. (June flows are @ 55% of the historical average)

NASA’s Earth Observatory says the dry weather is affecting the production of important Brazilian crops including coffee, corn, sugarcane and oranges. Yields for the corn crop could hit a five-year low and coffee production this year is forecasted to drop as much as 30% below normal levels.

In western Canada, rail cars carrying grain for export have been idled for weeks due to dangerous wildfires spanning five provinces and two territories.

Drought conditions in the Prairies have withered crops and in the northern US, forced farmers to sell their low-yielding wheat and barley as livestock feed. The region’s spring wheat prices recently hit their highest level in more than eight years.

A 21-year drought in the southwestern US (and into the northern states including Oregon) is depicted in the latest map by US Drought Monitor. Red areas are extreme drought, brown areas show exceptional drought. The current dry stretch started in 2000 and hasn’t let up, putting it second only to a highly arid period in the last 1500s.

With much of the world literally “on fire” due to severe drought/ lack of rain, and river levels so low it’s affecting the shipment of key exports, it should be apparent that climate change is happening in a big way, it’s a re-occurring phenomenon, and it’s elevating prices, year after year. In other words, we should consider climate change’s inflationary impacts on crop prices to be permanent — although they will vary from year to year, in magnitude, crop and location.

Financial blogger Charles Hugh Smith points out that, while dramatic price increases for cars, steaks, a basic breakfast and utility fees, among other things, can be construed as temporary inflation, the costs of production have increased in ways that are not temporary. Examples include wages which, once increased, never go down; the prices of inelastic goods like coffee, whose drinkers will not substitute another beverage just because of a price increase; and crops damaged by droughts, flooding, or in the case of Brazil, a freak summer frost that killed most of the young coffee trees.

Pandemic-related supply constraints might be temporary, currency devaluation could be transitory, although they are likely to be with us for at least the next two years, structural supply deficits, climate change, the global trend to electrify and decarbonize, are not temporary, or transitory. The inescapable conclusion: inflation compounds year after year and the purchasing power loss your currency has experienced will never be regained. Inflation is going to continue, so you better be prepared for scarcity, a lack of security of supply, and much higher prices.

Commodities

The inflationary cycle we are currently experiencing means now is a good time to be invested in commodities, which as mentioned, are a hedge against inflation.

The proof in the pudding? Earlier this week the Bloomberg Commodity Spot Index hit a 10-year high and is close to matching the record set in 2011, the height of the last commodities super-cycle. Materials with excellent price performances include copper, which in May hit a record high $10,460 a tonne and continues to trade in that range; brent crude oil which has doubled in price since November 2020; steel prices which are up over 200% since the start of the pandemic; and a number of agricultural commodities such as corn, soybeans and wheat.

There are demand-driven reasons for keeping prices higher, and structural issues surrounding the supply of certain mined commodities. First, the demand side.

China, the world’s second biggest economy and the top commodities consumer, has emerged from the pandemic relatively unscathed. Industrial production surged 6.6% in May and first-quarter GDP rose an astonishing 18.3%, the most since China began keeping quarterly records in 1992. High Chinese demand for iron ore used in steelmaking, copper, zinc and nickel, have kept the prices of these industrial metals buoyant.

The new “green economy” rejects dirty sources of energy and transportation, namely coal, oil, and natural gas. Instead, it relies on carbon-friendly modes of transport and energy production, including electric vehicles, renewable power, and energy storage, as well as mobile technology (5G) and rapid adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies needing increased computing power.

Transportation makes up 29% of global emissions, so transitioning from gas-powered cars and trucks to plug-in vehicles, as well as high-speed rail, is an important part of the plan to wean ourselves off fossil fuels.

However, to accomplish all of the above will require a colossal boost in the production of mined materials, including copper, silver, zinc, nickel, tin, lithium and palladium.

That is why Goldman Sachs and other influential voices are calling this the new commodities super-cycle.

President Biden’s trillion-dollar infrastructure bill currently making its way through the Senate, is aimed at transitioning the US transportation system to battery-powered vehicles and supporting renewable wind and solar energies over carbon-based sources like coal and natural gas.

Out of $621 billion allocated to transportation infrastructure, $174B will be made available for helping companies to make electric vehicles, and to build 500,000 charging stations across the country.

The transition from a fossil-fueled to a green economy isn’t only happening in the United States.

Energy companies in the European Union are planning on spending up to $1 trillion on renewable energy projects (yes you read that right) by 2030, while China is expected to spend a mind-blowing $15 trillion in order to make the shift from fossil fuels and meet its carbon reduction targets by 2060.

Growth will primarily come from solar, wind and energy storage, all of which will require copious metals.

Important as the demand story is, structural supply issues are arguably the more powerful driver of surging commodity prices.

The problems started with the covid-19 pandemic. Government-ordered restrictions at workplaces, including mines, led to copper mines in the top two producers, Chile and Peru, shutting down for at least part of 2020. Other mining companies had to cut capacity to comply with distancing measures.

Covid also messed up planning. When practically the entire world locked down in March, 2020, many lumber producers shuttered operations, sold off inventories and waited for better times. An unexpected housing surge owing to rock-bottom interest rates and people staying at home saw lumber prices shoot five times higher than pre-pandemic levels, reaching an all-time record $1,670 per thousand board feet.

Most businesses drew down inventories to the bare minimum to weather the downturn but were caught flat-footed when demand accelerated amid vaccination rollouts in early 2021.

A recent Forbes article explains not only why the pandemic has wreaked havoc on supply chains but why commodities are 2021’s number one investment:

Now companies don’t just need to make more stuff. They also have to restock their drawn-down inventories. The entire supply chain is playing catch up. And that chain begins with raw materials.

Meanwhile, material producers can’t keep up with demand because they simply didn’t expect this demand. And unlike a factory, they can’t flip the switch back to On and start making stuff. There’s a lead time to bring back and extend operations.

The result: the world is suddenly short on everything. Materials are being gobbled up like AirPods on Black Friday. And prices are going up.

Lead time is particularly relevant to mining; it can take up to 20 years for a new mine to come online, from discovery and resource delineation, to development, permitting, construction and finally, commercial production.

After the last commodities boom came to an abrupt halt in the mid-2010s, several mining companies savaged by plummeting metals prices were forced to take billion-dollar write-downs and enact fiscal discipline amid shareholder pressure.

The result was slashed spending on exploration, presaging a supply shortfall for a number of metals, especially copper. As BNN Bloomberg concisely puts it, The result is that while demand is surging, supply isn’t.

Indeed most of the low-hanging fruit has been picked, meaning that exploration companies and major/ mid-tier mining outfits need to go further afield to find new mineral deposits. This metal is often lower grade and more difficult to extract, requiring complex, and expensive, mining methods and metallurgical processing.

Over at 321gold.com, Bob Moriarty enforces this point when talking about copper. He states:

[T]he head grade of copper mines has gone from nearly 2% 25 years ago to less than 1%. In fact, some of the biggest copper mines in the world are mining .5, .6% copper. That means that it takes more tonnage to create the same number of pounds of copper. It’s more costly, it’s harder to extract. We’re not finding new deposits regularly, and permitting, dealing with governments, as we’re seeing in South America recently, is becoming even more challenging.

The fundamental secular themes are stronger than anything I’ve ever seen…

Meanwhile, natural resources are becoming increasingly scarce and we are witnessing industrial battery metals like copper facing a looming supply crunch. There simply aren’t many new mines of any significant scale coming online in the next decade.

So this is a helluva time to be a resource investor, it’s a remarkable time.

Picking up on Moriarty’s point about resource scarcity, this is one of the most important long-term, structural issues that underpin an investment in commodities.

The world’s population is expected to reach 9.7 billion by the year 2050 and 10.9 billion by 2100.

It’s estimated that to feed that number of people, global food production will need to increase from 25% to 70%.

The Earth might be big enough for the current 7.8 billion or even the 10 billion as Norman Borlaug, the father of the Green Revolution, believed. But the time is quickly coming when our sheer numbers will demand more than the planet can possibly supply.

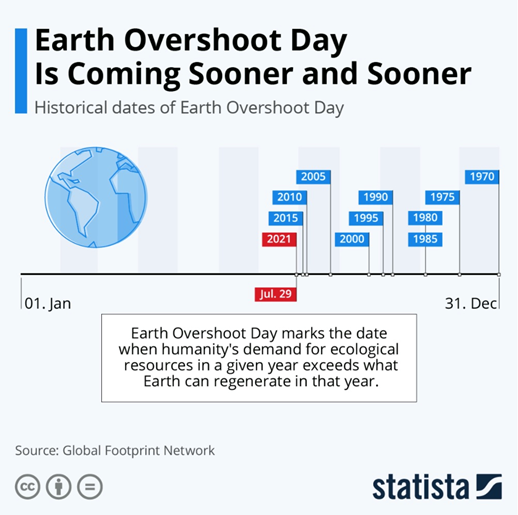

According to the Global Footprint Network (GFN) July 29 was Earth Overshoot Day 2021 — the day when humanity exhausted its ecological budget, when our consumption exceeded the environment’s renewable capacity for the entire year.

As the graphic below shows, Earth Overshoot Day is coming earlier and earlier each year, gradually moving from December 30 in 1970 to July 29 this year, according to GFN, via Zero Hedge.

They predict that by 2030, Earth Overshoot Day will be in June – meaning it will take two entire Earths to sustain our species’ consumption.

Conclusion

Inflation has nearly quadrupled from January to June 2021, making commodities, which nicely protect investments from rapid inflation and currency debasement, a good place to park your hard-earned cash.

Some investors like to play commodities by purchasing an exchange-traded fund (ETF), but we prefer to go straight into the metals we feel most bullish on. Buying shares in a producer is another common strategy, however history shows that junior explorers offer better leverage to rising metals prices. And they happen to be cheap. For the most part, companies exploring for copper, zinc, nickel, etc., have not matched soaring commodity prices. As Bob Moriarty puts it, and I agree with him, they offer a hell of an opportunity.

There are so many reasons to be bullish on commodities and as we outlined in the first half of this article, a lot to indicate that inflation is not going away anytime soon, thus setting up the conditions for a multi-year commodities up-trend.

To summarize, there has been a lack of spending on exploration and development, leading to current and looming supply shortages for a number of metals including copper, zinc, graphite and sulfide nickel. The mining companies in the mid-2010s basically ate each other and by shutting down exploration there was no accretive increase in reserves. Lower ore grades have also become a serious issue.

For agricultural commodities, severe droughts caused by or exacerbated by climate change have reduced yields and pushed prices higher especially in breadbasket nations like Brazil. There, the lack of rain is so extreme that rivers, an important transportation corridor, are drying up, forcing shippers to move goods overland at great expense. This will eventually be reflected in higher crop and food prices.

Meanwhile our fresh water supplies are being depleted at an alarming rate while we continue to wreck our environment with activities like fracking, which poisons groundwater, and litter rivers, lakes and oceans with plastic pollution.

Neither climate change nor pollution are temporary; they are both long-term trends that offer no easy solutions.

Natural resources are being used up faster than they can be replenished; this is another theme driving commodity prices higher. Countries that have the metals and crops needed to feed populations and fuel economic growth are guarding them more closely than previously; resource nationalism is on the rise.

For example Chile and Peru, the number one and two copper producers, are both seeking to raise the royalty tax on copper miners, while in the DRC, Africa’s top copper-mining country, the government banned the export of copper and cobalt concentrates — an action almost identical to what happened in Indonesia with nickel.

The United States is just waking up to the fact that China “is eating our lunch” to quote President Biden, and needs to invest heavily in infrastructure and mining, especially critical minerals needed for the shift toward electrification and decarbonization.

On top of the structural supply issues you have continued money-printing and borrowing to pay for exorbitant social programs and pandemic relief. Both are inflationary and provide another tailwind for commodities.

The sum total might just be the greatest opportunity to invest in resource stocks in history.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com